For many years I have dreamed about making a photographic sky atlas. This desire was sparked when I worked at California Institute of Technology (in the machine shop), where one day I was allowed to peruse their copy of the plates from the Palomar Sky Survey. Those plates from the POSS-I Survey, numbered 1,874. Half were "blue" plates and half were "red" of the identical areas. Each plate is roughly six degrees square on the sky.

Not wishing to expose (and pay for) more than 25 rolls of color film, I had the idea of making exposures that would approximate naked-eye views of the sky, but exposed so as to "see" with ten and 100 times the sensitivity of an ordinary eye. Using ISO 1600 film, that would have been 12 seconds and two minutes, ignoring reciprocity failure, or about twice that long to account for it. My scheme would have resulted in a set of about seventy exposures (less than three film rolls) to cover the northern sky and that portion of the southern sky visible from North America.

Time has always been the most deciding factor with me. I would need three or four observing sessions of several nights each, spaced around the year, from a dark location such as the top of a mountain in Colorado. In more recent years, now that digital photography is the norm, I realized that processing costs were now nearly zero, though printing was much the same if I wanted a "book" format. But I couldn't free up the time to go shoot the exposures.

Even more recently, the project has become moot. The successors to POSS-I, completed in the 1980s and 1990s, have been digitized into the Digital Sky Survey and incorporated into the "Sky" section of Google Earth. When you are looking at Google Sky, a notice at the bottom of the screen shows a credit line. Most of the sky is credited "© 2007 DSS Consortium". Some areas of the sky are instead credited to SDSS, the Sloan survey, and a few small bits to STSCI, which holds the images from the Hubble Space Telescope.

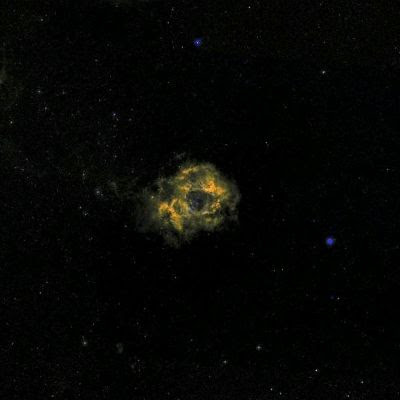

To see how closely I can realize my dream without shooting any film at all, I took a look at a portion of the sky near Orion, centered on the Rosette Nebula:

This image approximates a POSS-I plate pair, combined and colorized. It is about six degrees across. The nebula, which contains the open cluster NGC 2244, is one degree across, or twice as wide as the full moon. It would be a stupendous sight were it bright enough to see without the amplification provided by photography, film or digital. A six degree field of vision is about what you see with 7x to 10x binoculars. However, the next image is more representative of what such binoculars would show you from a really dark location:

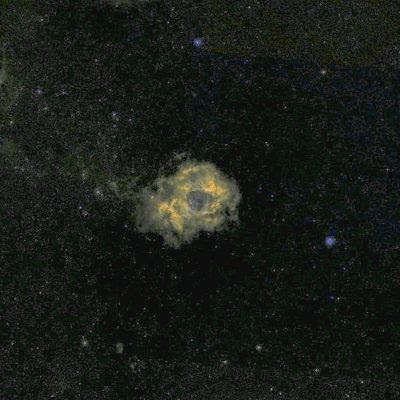

This image approximates a POSS-I plate pair, combined and colorized. It is about six degrees across. The nebula, which contains the open cluster NGC 2244, is one degree across, or twice as wide as the full moon. It would be a stupendous sight were it bright enough to see without the amplification provided by photography, film or digital. A six degree field of vision is about what you see with 7x to 10x binoculars. However, the next image is more representative of what such binoculars would show you from a really dark location: The eye just doesn't have the sensitivity to see more than the brightest bits of such a nebula, though a number of stars would be more visible than what is seen here. I reckon this image is probably a bit optimistic. The Rosette Nebula, as large as it is, wasn't named until it had been found photographically. It is dimmer than the great Orion nebula, the central portion of which is quite distinct when seen with binoculars.

The eye just doesn't have the sensitivity to see more than the brightest bits of such a nebula, though a number of stars would be more visible than what is seen here. I reckon this image is probably a bit optimistic. The Rosette Nebula, as large as it is, wasn't named until it had been found photographically. It is dimmer than the great Orion nebula, the central portion of which is quite distinct when seen with binoculars. On the other hand, adjusting the brightness of the image upward, we see what would show if the DSS had used a deeper baseline and higher gamma. With just a doubling of effective exposure, a myriad of faint background stars can be seen, and the nebula's details are even more distinct. If we could see this well, though, the sky would be rather confusing. Too much to see!

On the other hand, adjusting the brightness of the image upward, we see what would show if the DSS had used a deeper baseline and higher gamma. With just a doubling of effective exposure, a myriad of faint background stars can be seen, and the nebula's details are even more distinct. If we could see this well, though, the sky would be rather confusing. Too much to see!

No comments:

Post a Comment