kw: book reviews, fiction, rejections

Two books I didn't finish: Babylon Babies by Maurice G. Dantec (translated by Noura Wedell) and Titan by Ben Bova.

I am intrigued by some of the ideas in Babylon Babies, but was put off by the ugliness of the narrative. There is a way to handle war, even war and its atrocities, that doesn't drag the reader into a state of degradation. Most writers of the 1970s and earlier knew it, and few writers since have bothered to learn how. Dantec seems to revel in degradation for its own sake.

As I have written before, I take the Proverb seriously, "Guard your heart above all that you guard, for from it are the fountains of life." I guard my heart from trash as seriously as any wise person guards the stomach from damaging foods.

Thus, I hopped here and there, checking out the story line and the ideas; there is one of interest to me: that schizophrenics (at least some of them) are a stage in human evolution to a more comprehensive consciousness. However, the idea that a major, major evolutionary advance can take place in one or two generations simply exposes one's ignorance of natural selection, even of facilitated selection. The "punctuations" in Punctuated Equilibrium as proposed by Gould and Eldredge (see Punctuated Equilibrium Comes of Age ) encompass hundreds of generations, rather than the thousands to tens of thousands of generations of more traditional evolutionary theory.

Now, Titan, quite simply, I found very frustrating. Ben Bova has been one of my favorite writers since I got my first library card and discovered the Science Fiction section at the library. Titan is the latest of his Grand Tour series, and I suppose he plans to write an adventure about every planet and moon large enough to hold you down against a hard jump.

Bova has followed many of his fellow writers into the heads of his characters, particularly the villains and the merely venal. Mr. Bova, listen up: I don't care a rip about the though patterns of your creations. Leave that crap out!

Further, it seems no story can get published that isn't full of political machination. Titan is a middlin-big book, but in its timeline of half a year, compresses all the political and social twists of the French Revolution and the Terror.

I read the first third, then skipped to the end to see how it all wraps up. Getting the main villain a post-political job in the media was an interesting touch, and probably more like reality than the usual dénoument! But the final line turns this book into a clone of Sentinel (Clarke's story that was reworked into the movie 2001).

Having read—or declined to read—so many overly-plotted books these past few years, I got to thinking: I bet the writers are taking greater pains to hide their formula, either by cluttering them up with side branches or by making the formula much more complex. I realized these are the Maze and Labyrinth strategies.

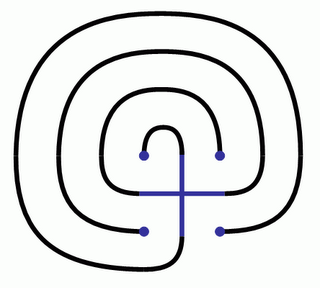

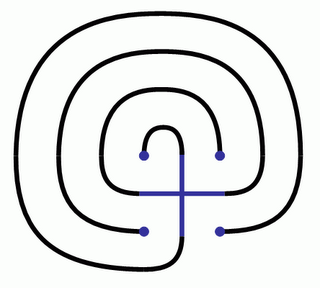

Did you ever consider, what is the difference between a Maze and a Labyrinth? Take a look at these two items:

Forget that one is rounded, the other square. Some folks call both of these Mazes, some call them both Labyrinths. But there is a significant difference. Whatever the shape, a Labyrinth has a single path, sometimes from end to end, but usually from a "mouth" to the center. Whatever the shape, a Maze has branches off the main path, dead ends, whether the goal is the center or an exit. Ergo, you cannot get lost in a Labyrinth!

Suffice it to say, the long-standing principle that all narrative must serve the purpose of pressing toward the goal, a well-written tale is a Labyrinth. Look again at the rounded Labyrinth above. To go from A to B, you'd go halfway there, wind around a bit, find yourself right next to A (if you could see it), then make much more rapid progress. You'd be certain to get there. A good story has twists and turns, and seeming setbacks, but gets to a goal in the end.

In the little maze, on the other hand, if you enter at the botton, taking the right branch takes you on a long, fruitless journey, while the left branch leads you past five shorter side branches, some of which you can discern with a peek around the corner. Now let's look at the smallest possible labyrinth.

This is a 3-circuit labyrinth. Although you must make four turns on the way to the center, there is no backtracking. This and the 7-circuit labyrinth above are of ancient design, and are easily drawn, if you care to try. I put the "starting cross" in dark blue. You draw the cross and four dots, then connect them with loops. The following diagram from The Labyrinth Society shows how to draw a 7-circuit labyrinth.

This is a 3-circuit labyrinth. Although you must make four turns on the way to the center, there is no backtracking. This and the 7-circuit labyrinth above are of ancient design, and are easily drawn, if you care to try. I put the "starting cross" in dark blue. You draw the cross and four dots, then connect them with loops. The following diagram from The Labyrinth Society shows how to draw a 7-circuit labyrinth.

By the way, the choice of making a left- or right-sided labyrinth is up to you. Mystics who make big hedge or path labyrinths in which to walk and meditate make much of the difference, but you'll find them both ways in all sorts of historical documents.

By the way, the choice of making a left- or right-sided labyrinth is up to you. Mystics who make big hedge or path labyrinths in which to walk and meditate make much of the difference, but you'll find them both ways in all sorts of historical documents.

From a literary point of view, the 3-circuit labyrinth is a fine structure for a straightforward short story; each turn makes further progress with no setbacks. (A typical story by O. Henry is even simpler: a long, straight shot with a quick, neck-wrenching turn at the end)

Many, many novels have a 7-circuit structure. The first path takes you halfway to the goal, then you circle back and forth, getting farther away, to find yourself near "square 1". Another path to the halfway point, loop around, almost make it, take three more loops that lead you farther away, until you are again at the halfway point, a third time, then it's a straight shot to the goal.

The next step in the sequence of "classical" labyrinths is 15-circuit. In Medieval times, other designs arose, and the 11-circuit variety shown here was popular.

These are quite a bit harder to draw. You can find advice galore with a little searching. The Labyrinth Society is a good starting point. While this labyrinth has eleven circuits, they are not complete circuits, but combinations of half-and quarter-circuits that make the path quite complex. There are, as with the 7-circuit labyrinth, four major thrusts toward the goal, but there are many more minor advances and setbacks (31 turns in all). I didn't read enough of Titan to determine its structure, but I suspect it is of this order of complexity.

These are quite a bit harder to draw. You can find advice galore with a little searching. The Labyrinth Society is a good starting point. While this labyrinth has eleven circuits, they are not complete circuits, but combinations of half-and quarter-circuits that make the path quite complex. There are, as with the 7-circuit labyrinth, four major thrusts toward the goal, but there are many more minor advances and setbacks (31 turns in all). I didn't read enough of Titan to determine its structure, but I suspect it is of this order of complexity.

And this labyrinth, in quadrants, is actually four 9-circuit labyrinths based on a Greek Key. I found it on Joe Edkin's Maze Page. If you take out one quadrant, and "circularize" the rest, you'd have the structure of a large trilogy.

And this labyrinth, in quadrants, is actually four 9-circuit labyrinths based on a Greek Key. I found it on Joe Edkin's Maze Page. If you take out one quadrant, and "circularize" the rest, you'd have the structure of a large trilogy.

Is life really like this? Can "labyrinthine" formula really match reality? Truly, it is a simplification. Real life is often more like a maze. I daren't consider how many blind alleys I've gone down, and had to backtrack.

What is "real life" anyway? To a person of faith, life has a goal, but we seldom know what it is...of course, heaven is considered a goal, but what is the goal of the life before we pass on? If we learn that at all, we learn it only in retrospect.