kw: book reviews, fiction, mysteries

Add a gaggle of truly nerdy students, ancient anarchists, a murderer (or several), and a couple of elderly eccentric detectives to the London underground, and stir well. You get not just a rollicking murder mystery, but a sort of "cousins of Holmes and Watson"—their crazy cousins. Bryant and May off the Rails by Christopher Fowler is apparently the eighth B&M mystery. Fortunately, there are few inside jokes to distract one, because as the author tells us right off, each volume stands by itself.

Arthur Bryant and John May are the lead detectives of the Peculiar Crimes Unit (I had to look it up; of course it is imaginary, but if only…). They manage to accomplish more by pottering around than a roomful of more "by the book" gumshoes. They are the odd couple of the genre, Bryant having the well-cluttered room, and mind, while May is more buttoned-down, though with a "culch pile" of his own. (Culch pile is my mother's word for that box or drawer or room full of miscellany we all accumulate and dare not get rid of. "Culch" derives from "culture".)

They are confronted with a criminal who has committed a murder during a burglary that went wrong, been apprehended, and escaped while killing a police guard with a skewer, an oversize ice pick. Now he is suddenly seen as much more dangerous, and the entire PCU is tasked to nab him, and given a rather brisk deadline. The natural habitat of this "Mr. Fox" is the Tube, the London underground (subway to an American), so the action focuses there.

The chapters have various viewpoints and voices. Certain ones are stream-of-consciousness of a desperate criminal, and I gradually became convinced that there were two or three, not just one murderer. The PCU are looking for a single perpetrator, but as the body count rises, it is difficult to imagine that the crimes are connected. Initial clues lead the detectives to a houseful of students, who seem very unlikely to be associated with any of the crimes. But Bryant has a feeling…

How big is the world's largest flash mob? One of the students does his best to assemble it, while the others play games of their own. Meanwhile, a witness who knows who Mr Fox really is has been attacked, but is getting out of the hospital, and the PCU uses him for bait. The denouement took me by surprise, as I'd picked out a different couple of persons for the real murderers.

That is the fun of these mysteries. The author's job is to mystify the reader, and the reader's to see through the deceptions. Mr. Fowler does a masterly job of it. I seldom like mysteries with a body count this high, but he certainly kept me going in this one.

Monday, January 31, 2011

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Maybe a planet

kw: science, citizen science, astronomy

In the past few weeks, I've learned to classify stars released by the Kepler Mission to the Planet Hunters project in Zooniverse. Two sayings of Thomas Edison come to mind as I check the light curve of star after star for the telltale feature that signals "planet here": "Invention is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration" and "I learned hundreds of things that don't make a light bulb." To date I've checked about 2,200 stars.

The Kepler instrument records the brightness of about 150,000 stars every thirty minutes. At the Planet Hunters web site, a thirty-day supply of such data are kept and parceled out, star by star, to interested hunters such as myself. The vast majority of the stars have a "curve", really a collection of dots representing the brightness measurements, that looks like this one, except for the little dip at the right end.

This is a typical quiet star, though there is a flare at day 4. The scatter in the data arise from the statistics of photon counting when you are taking short measurements from a 14th magnitude object. As you can see, nearly all the data are confined to the range 1.0075-1.0085. The band of light that draws the eye is mostly in 1.0078-1.0082. This star is a K type star of the same radius as our Sun, so it is probably K0 or K1. A planet the size of Earth would intercept only 0.0001 of its light (0.01%). Now look at the dip near day 30 (on the X axis). Its depth is about 0.00025, so if this is truly the transit of a planet, its size is 1.6 times that of earth. It is even more exciting that the transit takes so long. See the next image:

By counting the dots, I find 34, which means the transit took 17 hours. A transit of the Earth across the Sun, as observed from a nearby star, would take 13 hours, so the velocity is about 75% of Earth's about the Sun. This is a lighter star, so the orbital radius will be similar, but this is also a dimmer star, so I'd say it is near the outer edge of the star's habitable zone, perhaps in a 500-day orbit, comparable to a spot halfway from Earth to Mars in our solar system.

That is a lot to infer from 34 dots on a graph. It may be that there is no planet and this was something else. But it is exciting to realize that some of the features like this one, as seen by "citizen scientists" and cross checked by the project scientists, will indeed signal planets about some of the stars. They eventually expect to find hundreds.

I did a few rough calculations about this project. The chances of finding any random planet about a star of type F, G, or K, in an orbit ten days or longer (shorter ones don't interest me much) is one in thirty. If every star has planets, then the project as a whole could find five thousand. However, the chances of seeing a planet in the habitable zone are quite a bit smaller. For a G star, the chance is about one in 600. Double that (1/300) for a planet of a K star, about half of that (1/1,200) for a planet of an F star. K stars dominate, so overall, the number of planets at a habitable distance from their star, that we can detect with this project, is likely to be about 400 or 500. This number will be smaller if any substantial number of stars are totally planet-free. I count that unlikely.

In the past few weeks, I've learned to classify stars released by the Kepler Mission to the Planet Hunters project in Zooniverse. Two sayings of Thomas Edison come to mind as I check the light curve of star after star for the telltale feature that signals "planet here": "Invention is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration" and "I learned hundreds of things that don't make a light bulb." To date I've checked about 2,200 stars.

The Kepler instrument records the brightness of about 150,000 stars every thirty minutes. At the Planet Hunters web site, a thirty-day supply of such data are kept and parceled out, star by star, to interested hunters such as myself. The vast majority of the stars have a "curve", really a collection of dots representing the brightness measurements, that looks like this one, except for the little dip at the right end.

This is a typical quiet star, though there is a flare at day 4. The scatter in the data arise from the statistics of photon counting when you are taking short measurements from a 14th magnitude object. As you can see, nearly all the data are confined to the range 1.0075-1.0085. The band of light that draws the eye is mostly in 1.0078-1.0082. This star is a K type star of the same radius as our Sun, so it is probably K0 or K1. A planet the size of Earth would intercept only 0.0001 of its light (0.01%). Now look at the dip near day 30 (on the X axis). Its depth is about 0.00025, so if this is truly the transit of a planet, its size is 1.6 times that of earth. It is even more exciting that the transit takes so long. See the next image:

By counting the dots, I find 34, which means the transit took 17 hours. A transit of the Earth across the Sun, as observed from a nearby star, would take 13 hours, so the velocity is about 75% of Earth's about the Sun. This is a lighter star, so the orbital radius will be similar, but this is also a dimmer star, so I'd say it is near the outer edge of the star's habitable zone, perhaps in a 500-day orbit, comparable to a spot halfway from Earth to Mars in our solar system.

That is a lot to infer from 34 dots on a graph. It may be that there is no planet and this was something else. But it is exciting to realize that some of the features like this one, as seen by "citizen scientists" and cross checked by the project scientists, will indeed signal planets about some of the stars. They eventually expect to find hundreds.

I did a few rough calculations about this project. The chances of finding any random planet about a star of type F, G, or K, in an orbit ten days or longer (shorter ones don't interest me much) is one in thirty. If every star has planets, then the project as a whole could find five thousand. However, the chances of seeing a planet in the habitable zone are quite a bit smaller. For a G star, the chance is about one in 600. Double that (1/300) for a planet of a K star, about half of that (1/1,200) for a planet of an F star. K stars dominate, so overall, the number of planets at a habitable distance from their star, that we can detect with this project, is likely to be about 400 or 500. This number will be smaller if any substantial number of stars are totally planet-free. I count that unlikely.

Friday, January 28, 2011

Green fading to black

kw: book reviews, nonfiction, environmentalism

You buy E-15 Regular at the gasoline station, and wonder if you ought to get a flex-fuel vehicle that'll take E-85, assuming you can find any. You've put CFL's in most of the fixtures of your home, and wonder if it would still be worthwhile to purchase carbon offset credits. You go to the farmer's market for certified Organic groceries, whenever you can afford it, and wonder if buying "Beyond Organic" produce would be worth it.

In an ideal world, the answer to all three questions would be an unqualified "Yes!" In today's world, don't waste any more time; the answer is nearly always "No!!" That is, unless Heather Rogers is wrong on all counts. In her book Green Gone Wrong: How Our Economy is Undermining the Environmental Revolution, she went around the world to record and report just how three huge areas of popular environmental activism have worked out: Food, Shelter, and Transportation. The six chapters of the book are organized into these three areas.

Beginning in a farmer's market in New York City, and visiting a few of the farmers that sell there, she finds that none of the producers can afford to farm sustainably; all either have outside jobs to support their farm, or inherited the land so they have no mortgage to pay, yet they are still barely eking out a living. There is huge pressure to either "go conventional" or to get out of farming. And their customer base is small because their products cost so much more than factory-farmed, "conventional" produce. Many cannot be certified as Organic, because the paperwork and filing fees would swallow up all their available time and money.

In South America she finds that "Organic" is largely an illusion. Monocrops prevail, and the certifying bodies won't blow the whistle because they'll just be ignored anyway. Many fields are fertilized with chicken dung and waste from chicken farmers that fatten up their birds using definitely non-organic means, but this slips through a loophole in the Federal definition of Organic. And let's not even begin to discuss what happens to the indigenous people who inhabited the (former) forests—and managed them sustainably for centuries.

Amid multiple nations full of failed "green housing" projects, the author found a bright spot or two. One was in Freiburg, Germany, where the Vauban housing units demonstrate that green apartments can be very pleasant, comfortable, and economical. Startup costs are high, but the energy savings makes up for this in relatively few years. Rogers makes clear that it took a concerted effort by quite a number of social organizations, government and NGO groups, and citizen activism to create a social climate that was amenable. Freiburg is one of a few places where a Vauban could work.

Side note: Twenty-five years ago I had the opportunity to purchase a new SIPS home (Super Insulated Passive Solar), which included an air-to-air heat exchanger to allow good ventilation without losing heated or cooled air. Had the development been located convenient to anything, I'd have done it, but we decided location meant more. I wish I'd done it now, so I'd know more about living in such a home, because I want to have such a home built for us the next time we move.

Fully half the book is taken up with the three chapters regarding transportation. This is a big bugaboo of mine: E-15 or E-whatever is made from food, and in a world with one billion hungry people, we ought not be burning food to get around!!! Then we read of the author's visit to an oil palm plantation. The company's web site promises all kinds of good things, but the reality is a brutal rape of the Borneo rain forest to monocrop oil palms and the subjugation of the Dayak people. She could have titled this chapter "Every Promise Broken". It gets worse.

Back in Detroit, we find that our Big Three automakers can successfully market autos in Europe that get as much as 80 mpg, but claim that the U.S. market won't support them. Knowing how little such a car costs "over there", I can only answer, "Try me, dammit!" I once figured out that the fuel savings from a Prius (at 50mpg) didn't balance out the extra cost over a Corolla (at 32mpg), so we got the Corolla. It was a close thing. We're about to trade in a Camry, and the newer Prius is a very tempting alternative, as relative costs have come down. One of GM's Eurocar alternatives would be an even more tempting alternative, if importing one didn't almost double the cost of the car…and I might still do just that. My dad has railed for years about the engineered "failure" of GM's EV-1 electric. And if the author has it right, the automakers conspired over decades to dismantle the public transportation systems in all major U.S. cities to increase the market for autos. Once the trolleys are gone and the tracks paved over, it is hard to bring them back.

Finally, consider the "economics" of buying a carbon offset, where the organization promises to plant so many trees per ton of carbon you pay for. Will they really plant the trees? Maybe, if you're really lucky. Where? Oh, in the middle of somewhere that gets no rainfall, like central India. And, that promise to water and tend the saplings? Don't make me laugh! The author had a dangerously creepy moment in India, trying to get truthful answers about these things. I reckon she's lucky to have gotten away with her skin. Then think of this. Trees take twenty years to hit their stride and start absorbing lots of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But the carbon we've "offset" is going to be released right now, or it has been already. Then in fifty years the trees will die and their carbon will go back to the atmosphere. Will the atmosphere be ready for that in 2061?

In two closing chapters the author sums up the situation (bad and getting worse) and offers some slightly hopeful comments titled "Notes on the Possible". It is going to take a massive citizen effort, sustained over a couple-to-several decades, to straighten out these things. It is going to take a disaster to get people's attention, but will it be by then too late?

This book made my blood boil. Not at the author, I really appreciate what she has done. But at the venality of banal people who can find a way to subvert anything to their own benefit. A family proverb of mine, and perhaps one you've known: "The road to hell is paved with good intentions." The primary reason that is so true is that you are not in total charge of what happens to any of your well-intended efforts. Do not trust others, particularly when they are a world away, to ease your conscience. Do things where you control the outcome. As Mark Twain wrote, "Go ahead. Put all your eggs in one basket. Then watch that basket!"

You buy E-15 Regular at the gasoline station, and wonder if you ought to get a flex-fuel vehicle that'll take E-85, assuming you can find any. You've put CFL's in most of the fixtures of your home, and wonder if it would still be worthwhile to purchase carbon offset credits. You go to the farmer's market for certified Organic groceries, whenever you can afford it, and wonder if buying "Beyond Organic" produce would be worth it.

In an ideal world, the answer to all three questions would be an unqualified "Yes!" In today's world, don't waste any more time; the answer is nearly always "No!!" That is, unless Heather Rogers is wrong on all counts. In her book Green Gone Wrong: How Our Economy is Undermining the Environmental Revolution, she went around the world to record and report just how three huge areas of popular environmental activism have worked out: Food, Shelter, and Transportation. The six chapters of the book are organized into these three areas.

Beginning in a farmer's market in New York City, and visiting a few of the farmers that sell there, she finds that none of the producers can afford to farm sustainably; all either have outside jobs to support their farm, or inherited the land so they have no mortgage to pay, yet they are still barely eking out a living. There is huge pressure to either "go conventional" or to get out of farming. And their customer base is small because their products cost so much more than factory-farmed, "conventional" produce. Many cannot be certified as Organic, because the paperwork and filing fees would swallow up all their available time and money.

In South America she finds that "Organic" is largely an illusion. Monocrops prevail, and the certifying bodies won't blow the whistle because they'll just be ignored anyway. Many fields are fertilized with chicken dung and waste from chicken farmers that fatten up their birds using definitely non-organic means, but this slips through a loophole in the Federal definition of Organic. And let's not even begin to discuss what happens to the indigenous people who inhabited the (former) forests—and managed them sustainably for centuries.

Amid multiple nations full of failed "green housing" projects, the author found a bright spot or two. One was in Freiburg, Germany, where the Vauban housing units demonstrate that green apartments can be very pleasant, comfortable, and economical. Startup costs are high, but the energy savings makes up for this in relatively few years. Rogers makes clear that it took a concerted effort by quite a number of social organizations, government and NGO groups, and citizen activism to create a social climate that was amenable. Freiburg is one of a few places where a Vauban could work.

Side note: Twenty-five years ago I had the opportunity to purchase a new SIPS home (Super Insulated Passive Solar), which included an air-to-air heat exchanger to allow good ventilation without losing heated or cooled air. Had the development been located convenient to anything, I'd have done it, but we decided location meant more. I wish I'd done it now, so I'd know more about living in such a home, because I want to have such a home built for us the next time we move.

Fully half the book is taken up with the three chapters regarding transportation. This is a big bugaboo of mine: E-15 or E-whatever is made from food, and in a world with one billion hungry people, we ought not be burning food to get around!!! Then we read of the author's visit to an oil palm plantation. The company's web site promises all kinds of good things, but the reality is a brutal rape of the Borneo rain forest to monocrop oil palms and the subjugation of the Dayak people. She could have titled this chapter "Every Promise Broken". It gets worse.

Back in Detroit, we find that our Big Three automakers can successfully market autos in Europe that get as much as 80 mpg, but claim that the U.S. market won't support them. Knowing how little such a car costs "over there", I can only answer, "Try me, dammit!" I once figured out that the fuel savings from a Prius (at 50mpg) didn't balance out the extra cost over a Corolla (at 32mpg), so we got the Corolla. It was a close thing. We're about to trade in a Camry, and the newer Prius is a very tempting alternative, as relative costs have come down. One of GM's Eurocar alternatives would be an even more tempting alternative, if importing one didn't almost double the cost of the car…and I might still do just that. My dad has railed for years about the engineered "failure" of GM's EV-1 electric. And if the author has it right, the automakers conspired over decades to dismantle the public transportation systems in all major U.S. cities to increase the market for autos. Once the trolleys are gone and the tracks paved over, it is hard to bring them back.

Finally, consider the "economics" of buying a carbon offset, where the organization promises to plant so many trees per ton of carbon you pay for. Will they really plant the trees? Maybe, if you're really lucky. Where? Oh, in the middle of somewhere that gets no rainfall, like central India. And, that promise to water and tend the saplings? Don't make me laugh! The author had a dangerously creepy moment in India, trying to get truthful answers about these things. I reckon she's lucky to have gotten away with her skin. Then think of this. Trees take twenty years to hit their stride and start absorbing lots of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But the carbon we've "offset" is going to be released right now, or it has been already. Then in fifty years the trees will die and their carbon will go back to the atmosphere. Will the atmosphere be ready for that in 2061?

In two closing chapters the author sums up the situation (bad and getting worse) and offers some slightly hopeful comments titled "Notes on the Possible". It is going to take a massive citizen effort, sustained over a couple-to-several decades, to straighten out these things. It is going to take a disaster to get people's attention, but will it be by then too late?

This book made my blood boil. Not at the author, I really appreciate what she has done. But at the venality of banal people who can find a way to subvert anything to their own benefit. A family proverb of mine, and perhaps one you've known: "The road to hell is paved with good intentions." The primary reason that is so true is that you are not in total charge of what happens to any of your well-intended efforts. Do not trust others, particularly when they are a world away, to ease your conscience. Do things where you control the outcome. As Mark Twain wrote, "Go ahead. Put all your eggs in one basket. Then watch that basket!"

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Liniment time!

kw: current events, blizzards

We had six prior snowstorms since October, and in most cases, the forecast proved to be an overestimate. The worst was a four-inch fall (ten cm) that had started out as a prediction for eight to twelve inches (20-30 cm). The predictions made Tuesday were for rain with a little snow mixed in on Wednesday morning, followed by heavier snow Wednesday evening, in the four to eight inch range (10-20 cm).

I arose Wednesday morning (yesterday) to an inch of snow on the ground and more falling. I didn't bother to shovel, just went to work early before other cars were on the road, just before 6:00 AM. It snowed until noon. I went home at 2:30 PM and shoveled off four inches of snow in about an hour. We have more than a thousand square feet of pavement that needs shoveling, including a 220-foot sidewalk. My wife helped a little, but she fell a couple days ago and bruised a knee rather badly, so I asked her to take it easy. By dinner time I was sore, sore, sore. The wind was howling by 7:00 PM and snow was falling hard. I went to bed early after taking a gram of Ibuprofen.

This morning I could see there was a lot of snow. My wife at first said it looked like half a foot, but when I went out, it was clear we'd had over a foot, probably fourteen inches (36 cm). I had a large breakfast and began shoveling at 7:00 AM. At 8:30 I called work to tell them I'd take the day off. My wife helped a lot this time, but it was still after 11:00 AM when we finished. Snow is piled head high all down our driveway and at its end. I had another gram of Ibuprofen with lunch (my wife took a more normal dose of 200 mg). It is just wearing off as I write, so I'm going to take another gram and head for bed. Let's hope I recover quickly. There's another blizzard forecast for next week.

We had six prior snowstorms since October, and in most cases, the forecast proved to be an overestimate. The worst was a four-inch fall (ten cm) that had started out as a prediction for eight to twelve inches (20-30 cm). The predictions made Tuesday were for rain with a little snow mixed in on Wednesday morning, followed by heavier snow Wednesday evening, in the four to eight inch range (10-20 cm).

I arose Wednesday morning (yesterday) to an inch of snow on the ground and more falling. I didn't bother to shovel, just went to work early before other cars were on the road, just before 6:00 AM. It snowed until noon. I went home at 2:30 PM and shoveled off four inches of snow in about an hour. We have more than a thousand square feet of pavement that needs shoveling, including a 220-foot sidewalk. My wife helped a little, but she fell a couple days ago and bruised a knee rather badly, so I asked her to take it easy. By dinner time I was sore, sore, sore. The wind was howling by 7:00 PM and snow was falling hard. I went to bed early after taking a gram of Ibuprofen.

This morning I could see there was a lot of snow. My wife at first said it looked like half a foot, but when I went out, it was clear we'd had over a foot, probably fourteen inches (36 cm). I had a large breakfast and began shoveling at 7:00 AM. At 8:30 I called work to tell them I'd take the day off. My wife helped a lot this time, but it was still after 11:00 AM when we finished. Snow is piled head high all down our driveway and at its end. I had another gram of Ibuprofen with lunch (my wife took a more normal dose of 200 mg). It is just wearing off as I write, so I'm going to take another gram and head for bed. Let's hope I recover quickly. There's another blizzard forecast for next week.

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Doubling up for old eyes

kw: computers, home, photographs

For someone who is often called a power user, I can be remarkably behind the times. With my son's help I built a new computer this past summer, to replace an 8-year-old Dell machine. But I kept my monitor, a 19-inch 1280x1024 LCD.

For someone who is often called a power user, I can be remarkably behind the times. With my son's help I built a new computer this past summer, to replace an 8-year-old Dell machine. But I kept my monitor, a 19-inch 1280x1024 LCD.

It took a gift from my son to boost me into dual-monitor land. He decided to get a big monitor for gaming, a 28-inch 1920x1200 beast. He handed down his "small" monitor to me, not so small at 23 inches and 1680x1050, not quite HD.

Nearly all modern video adapters come with multiple plugs; the NVidia card in my new machine has three, a VGA (the "old" standard blue plug), a DVI, and a HDMI. Its documentation says any two can be used simultaneously, so we plugged the bigger monitor into the DVI port and kept the older monitor on the VGA one. Everything came up just fine. I imagine lots of people have done this already, years past even, but I am as tickled as if I'd invented it.

Both monitors have 86dpi resolution, compared to the setup where I work, with smaller dual monitors at 100dpi. This makes my home setup much easier on the eyes. All the text is 16% larger, so 12pt type looks like 14pt at home. This photo washes out the screens: I have a Word document open on the left, and a browser on the right, making it easier to do research while writing. No window switching required, just glance back and forth. I must report, however, that this does not double the rate at which I get ideas.

For someone who is often called a power user, I can be remarkably behind the times. With my son's help I built a new computer this past summer, to replace an 8-year-old Dell machine. But I kept my monitor, a 19-inch 1280x1024 LCD.

For someone who is often called a power user, I can be remarkably behind the times. With my son's help I built a new computer this past summer, to replace an 8-year-old Dell machine. But I kept my monitor, a 19-inch 1280x1024 LCD.It took a gift from my son to boost me into dual-monitor land. He decided to get a big monitor for gaming, a 28-inch 1920x1200 beast. He handed down his "small" monitor to me, not so small at 23 inches and 1680x1050, not quite HD.

Nearly all modern video adapters come with multiple plugs; the NVidia card in my new machine has three, a VGA (the "old" standard blue plug), a DVI, and a HDMI. Its documentation says any two can be used simultaneously, so we plugged the bigger monitor into the DVI port and kept the older monitor on the VGA one. Everything came up just fine. I imagine lots of people have done this already, years past even, but I am as tickled as if I'd invented it.

Both monitors have 86dpi resolution, compared to the setup where I work, with smaller dual monitors at 100dpi. This makes my home setup much easier on the eyes. All the text is 16% larger, so 12pt type looks like 14pt at home. This photo washes out the screens: I have a Word document open on the left, and a browser on the right, making it easier to do research while writing. No window switching required, just glance back and forth. I must report, however, that this does not double the rate at which I get ideas.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

A Darwinian view of abortion

kw: current events, abortion, evolution

When abortion was legalized about forty years ago, much was said about the elimination of back-alley "house of horrors" abortion clinics. I wish it were so. The case of Kermit Gosnell (I decline to use the title Dr.) shows that, somehow, the back alley is still with us. Some would say it shows the effect of a continuing social stigma, but the reality is much more banal. Clean clinics cost more, and far too many women have no medical insurance.

As much as I hate to admit it, abortion has a place in population moderation ("population control" bears too much hubris). The most modern methods of conception prevention, mis-named "birth control", are about 99% effective. It has been estimated and published a number of times that a woman in the Free World who uses the pill, an IUD, or a condom for every sexual encounter, intending to have no children during her thirty to forty years of fertility, will on average conceive three times. As a character in Jurassic Park said repeatedly, "Life will find a way." If a woman wants fewer than three children, what is she to do? RU-486 is one possibility, but only when used early. Abortion is the final resort.

In an ideal world with a generous economy, the cost of raising a child would not be a deterrent to having one. Welfare moms take note: you appear to be living in such an economy, albeit a bit skimpy on the "generous" side. But in the face of a planet that in forty years will be bearing nine billion persons, something has to give. The planetary economy will give out at some point.

However, there will always be wide differences in the number of children a particular woman or particular couple wishes to raise. Again, referring only to the free world, the cultural preference is now to have one or two children, not more. But some want more, and some want none. In Darwinian terms, what does this mean?

It means a lot of abortions. Abortions have become a factor in natural selection among humans. It can be imagined that the tendency to of some people to use abortion more than others is genetically determined, at least in part. People with those genetics will have fewer offspring than others, and many will have none. This will lead to a gradual reduction in "abortion-favoring" genes in the population. Generation after generation, the proportion of women who can "easily" choose abortion will decrease. Perhaps, if we are lucky, newer versions of the Pill will be developed that are more like 99.9% or 99.99% effective. Otherwise, the number of abortions will slowly decrease, and population will grow beyond UN projections.

Again, "Life will find a way," which in this case means population moderation is going to get harder as time goes on.

When abortion was legalized about forty years ago, much was said about the elimination of back-alley "house of horrors" abortion clinics. I wish it were so. The case of Kermit Gosnell (I decline to use the title Dr.) shows that, somehow, the back alley is still with us. Some would say it shows the effect of a continuing social stigma, but the reality is much more banal. Clean clinics cost more, and far too many women have no medical insurance.

As much as I hate to admit it, abortion has a place in population moderation ("population control" bears too much hubris). The most modern methods of conception prevention, mis-named "birth control", are about 99% effective. It has been estimated and published a number of times that a woman in the Free World who uses the pill, an IUD, or a condom for every sexual encounter, intending to have no children during her thirty to forty years of fertility, will on average conceive three times. As a character in Jurassic Park said repeatedly, "Life will find a way." If a woman wants fewer than three children, what is she to do? RU-486 is one possibility, but only when used early. Abortion is the final resort.

In an ideal world with a generous economy, the cost of raising a child would not be a deterrent to having one. Welfare moms take note: you appear to be living in such an economy, albeit a bit skimpy on the "generous" side. But in the face of a planet that in forty years will be bearing nine billion persons, something has to give. The planetary economy will give out at some point.

However, there will always be wide differences in the number of children a particular woman or particular couple wishes to raise. Again, referring only to the free world, the cultural preference is now to have one or two children, not more. But some want more, and some want none. In Darwinian terms, what does this mean?

It means a lot of abortions. Abortions have become a factor in natural selection among humans. It can be imagined that the tendency to of some people to use abortion more than others is genetically determined, at least in part. People with those genetics will have fewer offspring than others, and many will have none. This will lead to a gradual reduction in "abortion-favoring" genes in the population. Generation after generation, the proportion of women who can "easily" choose abortion will decrease. Perhaps, if we are lucky, newer versions of the Pill will be developed that are more like 99.9% or 99.99% effective. Otherwise, the number of abortions will slowly decrease, and population will grow beyond UN projections.

Again, "Life will find a way," which in this case means population moderation is going to get harder as time goes on.

Monday, January 24, 2011

Eels are people too

kw: book reviews, nonfiction, natural history, fish, eels

This large freshwater eel from Singapore is typical of Asian eels in its mottled color, but is otherwise similar to eels found worldwide (Image from The Lazy Lizard's Tales). Most freshwater eels are dark brown or black. A strange fact: The food provided by Indians to the English immigrants, commemorated in Thanksgiving celebrations, was largely an eel feast, with venison a minor component.

This large freshwater eel from Singapore is typical of Asian eels in its mottled color, but is otherwise similar to eels found worldwide (Image from The Lazy Lizard's Tales). Most freshwater eels are dark brown or black. A strange fact: The food provided by Indians to the English immigrants, commemorated in Thanksgiving celebrations, was largely an eel feast, with venison a minor component.

Freshwater Eels are catadromous, meaning they move downstream and out into the ocean to breed; "cata" means "down". This is in contrast to salmon and shad, which are anadromous, moving from the ocean upstream to breed; "ana" means "up". Just where the eels breed is still not known in any detail, and eels remain very mysterious, as described in Eels: An Exploration, From New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World's Most Mysterious Fish by James Prosek. Eels from around the Atlantic are known to breed somewhere in the Sargasso Sea, and Asian eels have very recently been caught, dying, a few days after breeding, but despite a century's diligent effort, they have never been observed breeding.

Author James Prosek traveled the world, initially searching for the facts of eel biology and ecology. After several years he found he was learning much more of eel folklore and mythology. While in most places eels are a food animal, the Lasialap people of Pohnpei (formerly Ponape) Island in Micronesia believe they are descended from eels, and look upon the eating of eels with horror. Although the Maori of New Zealand eat eels, their folklore is filled with cautionary tales of those who would abuse them, and with stories of the taniwha (pronounced "tanifa"), or guardian eels.

Like every other ocean resource, the eel fishery is collapsing worldwide. This has led to an immense trade in glass eels, the first post-larval stage when they are 4-5 cm in length, which are used to stock rivers and lakes for "fattening up". Current prices for glass eels are a few hundred dollars per pound. Imagine what a five-ton shipment of glass eels from Maine is worth!

One of the author's long-term friends has been Ray Turner, who maintains an eel weir near Peas Eddy in New York State. Each year he endeavors to capture something like a thousand eels from the many thousands who migrate downstream into the Delaware River each year. When the weather doesn't cooperate, he'll capture only a fraction of that. Prosek returned year after year to Peas Eddy, and was able to gradually participate in most aspects of the commercial eel business of which Turner is a part.

Though freshwater eel numbers from all nineteen species are crashing nearly everywhere, there is as yet no designation of them as either endangered or threatened, particularly in the U.S. Activists that Prosek got to know believe this is political. Eels are found throughout North American watersheds, and an Endangered designation would disrupt activities along all the continent's rivers. But it is precisely those activities, damming for hydropower and "recreation", and commerce with its effluents, that prevent eels from completing their life cycles. At one time the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River were the premier eel growing areas; no more. There is too much that is in their way now. The Delaware is the main river of the Eastern American seaboard that is not dammed every few miles, and is the last major eel growing region. The nearby Susquehanna River is nearly eel-free now. If eels were more "warm and cuddly"—they happen to be cold and slimy—they would probably get more respect. There are few who stand up for them.

There is an interesting parallel between the history of the Atlantic eel species and that of the green sea turtles. Both migrate thousands of miles to breed. Both are about 200 million years old. Both apparently began breeding, the turtles on the Azores, the eels in mid-water, when the Atlantic Ocean first opened. As the ocean widened over the millennia, both gradually adapted and honed their navigation skills, so as to find their breeding grounds as these were taken farther and farther from the coasts of America and Africa and Europe by continental motions. Prosek tells the story of the eels' evolution, and I happened to know already of that of the turtles.

The book is a real eye-opener. The eels' story is a lot like our story. They live up to 100 years, just as people do. They are easily tamed, and have personalities. They have become a worldwide success over those millions of years, but this upstart primate species is taking over the rivers, to the point that eels are getting squeezed out. Only in places where they are revered are they in any sense still thriving. The book, first conceived as a recipe book, became a spiritual journey for its author. This mysterious fish, which can travel overland if needed to reach its goal, deserves to be better known.

This large freshwater eel from Singapore is typical of Asian eels in its mottled color, but is otherwise similar to eels found worldwide (Image from The Lazy Lizard's Tales). Most freshwater eels are dark brown or black. A strange fact: The food provided by Indians to the English immigrants, commemorated in Thanksgiving celebrations, was largely an eel feast, with venison a minor component.

This large freshwater eel from Singapore is typical of Asian eels in its mottled color, but is otherwise similar to eels found worldwide (Image from The Lazy Lizard's Tales). Most freshwater eels are dark brown or black. A strange fact: The food provided by Indians to the English immigrants, commemorated in Thanksgiving celebrations, was largely an eel feast, with venison a minor component.Freshwater Eels are catadromous, meaning they move downstream and out into the ocean to breed; "cata" means "down". This is in contrast to salmon and shad, which are anadromous, moving from the ocean upstream to breed; "ana" means "up". Just where the eels breed is still not known in any detail, and eels remain very mysterious, as described in Eels: An Exploration, From New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World's Most Mysterious Fish by James Prosek. Eels from around the Atlantic are known to breed somewhere in the Sargasso Sea, and Asian eels have very recently been caught, dying, a few days after breeding, but despite a century's diligent effort, they have never been observed breeding.

Author James Prosek traveled the world, initially searching for the facts of eel biology and ecology. After several years he found he was learning much more of eel folklore and mythology. While in most places eels are a food animal, the Lasialap people of Pohnpei (formerly Ponape) Island in Micronesia believe they are descended from eels, and look upon the eating of eels with horror. Although the Maori of New Zealand eat eels, their folklore is filled with cautionary tales of those who would abuse them, and with stories of the taniwha (pronounced "tanifa"), or guardian eels.

Like every other ocean resource, the eel fishery is collapsing worldwide. This has led to an immense trade in glass eels, the first post-larval stage when they are 4-5 cm in length, which are used to stock rivers and lakes for "fattening up". Current prices for glass eels are a few hundred dollars per pound. Imagine what a five-ton shipment of glass eels from Maine is worth!

One of the author's long-term friends has been Ray Turner, who maintains an eel weir near Peas Eddy in New York State. Each year he endeavors to capture something like a thousand eels from the many thousands who migrate downstream into the Delaware River each year. When the weather doesn't cooperate, he'll capture only a fraction of that. Prosek returned year after year to Peas Eddy, and was able to gradually participate in most aspects of the commercial eel business of which Turner is a part.

Though freshwater eel numbers from all nineteen species are crashing nearly everywhere, there is as yet no designation of them as either endangered or threatened, particularly in the U.S. Activists that Prosek got to know believe this is political. Eels are found throughout North American watersheds, and an Endangered designation would disrupt activities along all the continent's rivers. But it is precisely those activities, damming for hydropower and "recreation", and commerce with its effluents, that prevent eels from completing their life cycles. At one time the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River were the premier eel growing areas; no more. There is too much that is in their way now. The Delaware is the main river of the Eastern American seaboard that is not dammed every few miles, and is the last major eel growing region. The nearby Susquehanna River is nearly eel-free now. If eels were more "warm and cuddly"—they happen to be cold and slimy—they would probably get more respect. There are few who stand up for them.

There is an interesting parallel between the history of the Atlantic eel species and that of the green sea turtles. Both migrate thousands of miles to breed. Both are about 200 million years old. Both apparently began breeding, the turtles on the Azores, the eels in mid-water, when the Atlantic Ocean first opened. As the ocean widened over the millennia, both gradually adapted and honed their navigation skills, so as to find their breeding grounds as these were taken farther and farther from the coasts of America and Africa and Europe by continental motions. Prosek tells the story of the eels' evolution, and I happened to know already of that of the turtles.

The book is a real eye-opener. The eels' story is a lot like our story. They live up to 100 years, just as people do. They are easily tamed, and have personalities. They have become a worldwide success over those millions of years, but this upstart primate species is taking over the rivers, to the point that eels are getting squeezed out. Only in places where they are revered are they in any sense still thriving. The book, first conceived as a recipe book, became a spiritual journey for its author. This mysterious fish, which can travel overland if needed to reach its goal, deserves to be better known.

Friday, January 21, 2011

Sledding the State Capitol

kw: pastimes, childhood, sledding

To the right in this image is the Utah State Capitol building in Salt Lake City. (Click to see a larger, clearer image. The image is looking due west.) Lined up with the Capitol building and heading south is State Street, and the next major street to the west is Main. The major east-west street that passes the large building on the left is North Temple Street. The Mormon Tabernacle is just out of the picture to the left.

To the right in this image is the Utah State Capitol building in Salt Lake City. (Click to see a larger, clearer image. The image is looking due west.) Lined up with the Capitol building and heading south is State Street, and the next major street to the west is Main. The major east-west street that passes the large building on the left is North Temple Street. The Mormon Tabernacle is just out of the picture to the left.

When I was a child the city police would block off that 1/3-mile stretch of State Street for sledding. Parents could drive their children to the entrance to the Capitol grounds, then drive over to Main and down to North Temple, and back over to State to pick them up. Younger kids might be driven back to the top; older kids got to walk back up. I remember that we did this only once, when I was about eight (1955 or early 1956). This hill has about a 6% grade, just perfect for sledding. We were there a couple of hours, time enough to slide down seven or eight times.

I suppose it was done on either a holiday or a Saturday when there was little business along State Street and none at the Capitol. Who can imagine in these days being allowed to sled on a major city street, no matter how nice its hill?

To the right in this image is the Utah State Capitol building in Salt Lake City. (Click to see a larger, clearer image. The image is looking due west.) Lined up with the Capitol building and heading south is State Street, and the next major street to the west is Main. The major east-west street that passes the large building on the left is North Temple Street. The Mormon Tabernacle is just out of the picture to the left.

To the right in this image is the Utah State Capitol building in Salt Lake City. (Click to see a larger, clearer image. The image is looking due west.) Lined up with the Capitol building and heading south is State Street, and the next major street to the west is Main. The major east-west street that passes the large building on the left is North Temple Street. The Mormon Tabernacle is just out of the picture to the left.When I was a child the city police would block off that 1/3-mile stretch of State Street for sledding. Parents could drive their children to the entrance to the Capitol grounds, then drive over to Main and down to North Temple, and back over to State to pick them up. Younger kids might be driven back to the top; older kids got to walk back up. I remember that we did this only once, when I was about eight (1955 or early 1956). This hill has about a 6% grade, just perfect for sledding. We were there a couple of hours, time enough to slide down seven or eight times.

I suppose it was done on either a holiday or a Saturday when there was little business along State Street and none at the Capitol. Who can imagine in these days being allowed to sled on a major city street, no matter how nice its hill?

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Can medicine be healed?

kw: book reviews, nonfiction, medicine, pharmaceutical industry

In 1996 I was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), partly by symptoms and partly by a blood test for Rheumatoid Factor (RF). A normal RF level is less than 60 units per cc of blood (some labs use 50 or even 40). My level was 100 u/cc. At the advice of a doctor named Oliver, I also had a test for antibodies to the Mycoplasma organism, and that test was positive. After some discussion and disputation with my doctor, I was treated with tetracycline, on a regimen Dr. Oliver recommended to my doctor, and after three years I was free of symptoms. In 2009, after a lapse of ten years, I was re-tested for RF and other, newer clinical indicators. I was then told I have no clinical signs of RA. I had it, and now I don't; I was cured. Yet most doctors, if you ask about treating RA with antibiotics, will tell you it is a quack remedy.

My father had found Doctor Oliver years earlier, looking for an effective treatment for his own arthritis. Dr. Oliver was a colleague of Dr. Thomas M. Brown, who developed the understanding that arthritis is a bacterial allergy, treatable by antibiotics to eliminate the bacteria. You can learn more from the resources provided at The Road Back Foundation, named based on Dr. Brown's first book, The Road Back. More recent editions by his co-author Henry Scammell are titled Arthritis Breakthrough.

Most RA specialists treat the symptoms (not the disease) with a series of quite expensive treatments, including gold injections and various semi-steroid and steroid pain management medicines. There is a sort of standard round of treatments that lasts about twenty years before they declare they are out of effective treatments, and leave you to the tender mercies of NSAIDs such as Advil, just at the age when a large dose of Advil is most likely to cause a perforation of your stomach lining. During that twenty years, you and your insurance company together will spend about $100,000 on treatments.

A one-year supply of tetracycline costs less than $30. It takes three to five years to cure arthritis when it is caught early enough. In my father's case, his infection has proven too advanced to cure completely, so he is still taking tetracycline, at a cost of $30 yearly. For him, tetracycline is like a vitamin. Without it, he soon loses the ability to walk without pain.

I have written a number of times that the main problem with American medicine is that it has become a big business. Little did I know. I just finished reading White Coat, Black Hat: Adventures on the Dark Side of Medicine by Carl Elliott (M.D., PhD, if I read his CV right). I am horrified. I am also fortified, when I run up against my doctor saying he relies on "evidence based medicine." As shown in the second chapter of the book, the "evidence" is largely fudged! But I'm getting ahead of myself. I'll go chapter by chapter.

One rule I follow as strictly as I can, is to request generic drugs whenever possible. This is not primarily to keep my money out of drug company coffers (though that is a nice side benefit), but it restricts the pool of drugs to those that have been used for ten or twenty years, because they are out of patent, and have at least not been taken off the market for excessive danger. Their effectiveness has also become pretty well known. Few "younger" drugs are likely to be significantly better. Make your doctor prove that a "hot drug" is really so much better it is worth the extra cost and extra risk. Don't be a passive patient. You might know more than your doctor does!

In 1996 I was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), partly by symptoms and partly by a blood test for Rheumatoid Factor (RF). A normal RF level is less than 60 units per cc of blood (some labs use 50 or even 40). My level was 100 u/cc. At the advice of a doctor named Oliver, I also had a test for antibodies to the Mycoplasma organism, and that test was positive. After some discussion and disputation with my doctor, I was treated with tetracycline, on a regimen Dr. Oliver recommended to my doctor, and after three years I was free of symptoms. In 2009, after a lapse of ten years, I was re-tested for RF and other, newer clinical indicators. I was then told I have no clinical signs of RA. I had it, and now I don't; I was cured. Yet most doctors, if you ask about treating RA with antibiotics, will tell you it is a quack remedy.

My father had found Doctor Oliver years earlier, looking for an effective treatment for his own arthritis. Dr. Oliver was a colleague of Dr. Thomas M. Brown, who developed the understanding that arthritis is a bacterial allergy, treatable by antibiotics to eliminate the bacteria. You can learn more from the resources provided at The Road Back Foundation, named based on Dr. Brown's first book, The Road Back. More recent editions by his co-author Henry Scammell are titled Arthritis Breakthrough.

Most RA specialists treat the symptoms (not the disease) with a series of quite expensive treatments, including gold injections and various semi-steroid and steroid pain management medicines. There is a sort of standard round of treatments that lasts about twenty years before they declare they are out of effective treatments, and leave you to the tender mercies of NSAIDs such as Advil, just at the age when a large dose of Advil is most likely to cause a perforation of your stomach lining. During that twenty years, you and your insurance company together will spend about $100,000 on treatments.

A one-year supply of tetracycline costs less than $30. It takes three to five years to cure arthritis when it is caught early enough. In my father's case, his infection has proven too advanced to cure completely, so he is still taking tetracycline, at a cost of $30 yearly. For him, tetracycline is like a vitamin. Without it, he soon loses the ability to walk without pain.

I have written a number of times that the main problem with American medicine is that it has become a big business. Little did I know. I just finished reading White Coat, Black Hat: Adventures on the Dark Side of Medicine by Carl Elliott (M.D., PhD, if I read his CV right). I am horrified. I am also fortified, when I run up against my doctor saying he relies on "evidence based medicine." As shown in the second chapter of the book, the "evidence" is largely fudged! But I'm getting ahead of myself. I'll go chapter by chapter.

- Chapter 1, "The Guinea Pigs" – Phase I trials of a new drug test whether it has acceptable levels of side effects and how safe it is. Such trials often involve unpleasant procedures such as colonoscopies or frequent blood testing, and often require residential sequestering of some or all subjects. So trial subjects are paid, and most such trials are dominated by "professional guinea pigs" who make a living at it. Many will lie about their state of health, how recently they may have done a previous trial, and other things that invalidate the results of the trial. Bottom line: Phase I trials of new drugs are often worthless, which is why every couple of years there is a problem with a Phase II or Phase III trial, such as patients dying of a supposedly "safe" dose.

- Chapter 2, "The Ghosts" – Every pharmaceutical company employs teams of writers who write a great variety of materials, some disguised as journalism, some being direct press releases, but many being articles intended for publication in medical journals. These articles report the results of drug trials as favorably as possible. They are published under the name of a medical researcher, who has usually been paid for the use of his or her name. Sometimes the "author" never sees the article. A bit of statistical lingo here: A "significant" result is one that is "different from a null hypothesis at the 0.95 level". That means if you do something twenty times, you'll probably get a "significant" result at least once, just by chance. Then there are "outliers". A statistical analyst is allowed to throw out an extra-high or extra-low result, claiming it was "experimental error". This will often change a finding of "nothing of significance" to "significant." Then there's the "drawer veto". A trial that yields negative results is often left to molder in a drawer while the trial is repeated (if the company has enough money). The repeated trial will show a better result about half the time, and by throwing out an outlier or two, a "significant" result can he claimed, so they go to publication, pay an unwitting "author", and get "scientific" backing, or "evidence" that the new drug works. Bottom line: Several studies of medical literature have been done, tracing the source of articles about specific drugs. In every case, more than half (up to 75%) of the articles were ghostwritten by writers in the employ of a drug company. "Evidence based medicine" is illusory, at least as regards drug trials.

- Chapter 3, "The Detail Men" – This is the older term for "Reps" or drug company representatives, the very personable, very attractive, very well dressed salespersons who show up at a doctor's office, often with pizza for everyone on the staff, with baskets full of pens, note pads, wall calendars, perhaps anatomical posters, all helpfully branded with the company's logo, and of course, samples of the current "hot drugs". I have yet to see a physician's office that was free of drug company trinkets. Dr. Elliott shows with overwhelming evidence that doctors are strongly influenced by even small gifts. Public databases show that after a Rep visit, prescriptions for the "hot drugs" skyrocket. Bottom Line: Your doctor's suggestion for a prescription is quite likely to be influenced by whose Rep visited the office last, more than by the exact medical needs of your case.

- Chapter 4, "The Thought Leaders" – These are public figures, manufactured out of mild-mannered researchers by generous stipends, star/celebrity treatment, lots of force-fed PowerPoint presentations helpfully written by drug company staff. They speak at conventions, often organized by the companies; they get on TV talk shows; they give press briefings; and generally promote the drug company's interests, but nearly never mention the source of their paycheck. Bottom Line: The people you doctor is listening to are most likely KOLs, Key Opinion Leaders, in the employ of large pharmaceutical companies.

- Chapter 5, "The Flacks" – At this point, I confess I was becoming overwhelmed by the pervasive manipulation of perception the book's author was describing. It got worse. These are the Public Relations specialists. They take a page from the fellow who first learned to sell pianos by selling the public on the idea that every home ought to have a Music Room, even if it was just a corner of the parlor. What else ya gonna put in your music room? They take it much further, preparing the public's perception of a drug for years before it passes through its trials (if it does). The rather recent FDA ruling that allowed drugs to be marketed directly to the public (one third of all TV ads, by my count), has just upped the ante. Doctors who decline to prescribe the latest "hot drug" to their anxious patients soon lose those patients to more complaisant doctors. Bottom Line: The people you are listening to are a different kind of KOL, the ad company writer.

- Chapter 6, "The Ethicists" – Imagine a warehouse full of gold, surrounded by a pack of attack dogs. But! The dogs are all munching on steaks supplied by your friendly local gold thief while he waltzes in and out with a wheelbarrow. Do you really need details? A great many, perhaps most, ethical review professionals are in the employ of the drug companies. They are allowed certain freedoms, and even encouraged to criticize certain abuses. But those few who allow themselves to become too independent, who expose the more sensitive misdeeds of their benefactor, find themselves without funding, and may find it hard to secure employment. Bottom Line: Where you stand depends on where you sit. American Big Pharma is doing their darndest to make sure everyone who matters is sitting right where they want them.

One rule I follow as strictly as I can, is to request generic drugs whenever possible. This is not primarily to keep my money out of drug company coffers (though that is a nice side benefit), but it restricts the pool of drugs to those that have been used for ten or twenty years, because they are out of patent, and have at least not been taken off the market for excessive danger. Their effectiveness has also become pretty well known. Few "younger" drugs are likely to be significantly better. Make your doctor prove that a "hot drug" is really so much better it is worth the extra cost and extra risk. Don't be a passive patient. You might know more than your doctor does!

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Do we turn them away?

kw: medicine, insurance, mandates

When my grandmother had a stroke in 1972 she was taken to a hospital, where she died the next day. My mother remarked later, "If she had awoken in the hospital, she'd have died of apoplexy." It was her first visit to a hospital since 1918, when her first child was born. That birth experience so disgusted her that she had her younger children, including my mother, on the kitchen table, delivered by my grandfather. She never partook of medical services again, consciously at least.

From 1918 to 1972 is 54 years. More than a half century during which she spent not a penny on medical services. That is how she wanted it. More to the point, when my grandfather became troubled by dementia, probably Alzheimer's although it was called "hardening of the arteries" in the 1960s, she cared for him at home, right up until his death at age 75.

My grandparents ran a family business their entire lives together. Their only employees were their children. They had no medical insurance. Being well-to-do, when they needed a doctor to see to a sick child, and that was very rare, they simply paid for it. What would they have paid for insurance, had they had any?

The current medical insurance premium for a family of five is about $14,000 yearly, or nearly $1,200 per month. If you have insurance, that is what is being paid, probably by your employer. That is what it has to be because the average American family uses on average more than $1,000 in medical services monthly. Now if we back out inflation and other changes in the value of money over time, consider what fifty years of such insurance would cost: $700,000. About three-quarters of a million dollars (current 2010 dollars). This is the level of payment that every family will be required to pay in medical insurance premiums according to the "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act", often nicknamed Obamacare.

I am inclined to bridle strongly at the notion that people should be forced to buy medical insurance. The original bill was sold to the American public as a way to make medical insurance "available to all" at affordable rates. Making something available is definitely not the same as making it mandatory. On the other hand, what if we don't? What if the effort to repeal PPACA were to succeed? And further, what if a new law were passed that provided insurance to all who wanted it, at the same cost to all (that'll be the day!), but did not force people to buy any?

A single consideration illuminates the problem. Will there also be a mandate to care for everyone, insured or not? If there is, what incentive will people have to pay for insurance? Or will there be an explicit proviso that hospitals and doctors can decline to care for someone who is not insured and cannot privately pay? Will they actually turn patients away at the door? Will ambulance crews be required to check the insurance status and solvency of a person before taking them to the emergency room? "That one's not insured, leave him there." Really?

Though I am conservative, a registered Republican, I must reluctantly affirm that this is just like automobile insurance, which is currently a requirement in nearly every state, and will eventually be a national requirement. If you are alive, you will pay medical insurance premiums. Life is uncertain. You cannot guarantee that you will live fifty years without the need to get medical help. My poor grandmother would be spitting mad at such a requirement. It can't be helped.

I look back at my working career, in which I have had medical insurance since 1967. It has proportionally risen the most in recent years, so I can only give an approximate figure, but in current dollars, the premiums, mostly company paid, total about $400,000. Would I like to have that money in my bank account instead? You bet. But I've had some expensive medical stuff done, so I don't grudge it.

There are bound to be horror stories of all kinds, no matter what kind of medical insurance law we live under in the next fifty years. Our task as a civilized society is to continue to revise laws to minimize the horror stories, and to make right what we can when one occurs. That is what we have done for 234 years so far, with variable success. It beats anarchy.

When my grandmother had a stroke in 1972 she was taken to a hospital, where she died the next day. My mother remarked later, "If she had awoken in the hospital, she'd have died of apoplexy." It was her first visit to a hospital since 1918, when her first child was born. That birth experience so disgusted her that she had her younger children, including my mother, on the kitchen table, delivered by my grandfather. She never partook of medical services again, consciously at least.

From 1918 to 1972 is 54 years. More than a half century during which she spent not a penny on medical services. That is how she wanted it. More to the point, when my grandfather became troubled by dementia, probably Alzheimer's although it was called "hardening of the arteries" in the 1960s, she cared for him at home, right up until his death at age 75.

My grandparents ran a family business their entire lives together. Their only employees were their children. They had no medical insurance. Being well-to-do, when they needed a doctor to see to a sick child, and that was very rare, they simply paid for it. What would they have paid for insurance, had they had any?

The current medical insurance premium for a family of five is about $14,000 yearly, or nearly $1,200 per month. If you have insurance, that is what is being paid, probably by your employer. That is what it has to be because the average American family uses on average more than $1,000 in medical services monthly. Now if we back out inflation and other changes in the value of money over time, consider what fifty years of such insurance would cost: $700,000. About three-quarters of a million dollars (current 2010 dollars). This is the level of payment that every family will be required to pay in medical insurance premiums according to the "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act", often nicknamed Obamacare.

I am inclined to bridle strongly at the notion that people should be forced to buy medical insurance. The original bill was sold to the American public as a way to make medical insurance "available to all" at affordable rates. Making something available is definitely not the same as making it mandatory. On the other hand, what if we don't? What if the effort to repeal PPACA were to succeed? And further, what if a new law were passed that provided insurance to all who wanted it, at the same cost to all (that'll be the day!), but did not force people to buy any?

A single consideration illuminates the problem. Will there also be a mandate to care for everyone, insured or not? If there is, what incentive will people have to pay for insurance? Or will there be an explicit proviso that hospitals and doctors can decline to care for someone who is not insured and cannot privately pay? Will they actually turn patients away at the door? Will ambulance crews be required to check the insurance status and solvency of a person before taking them to the emergency room? "That one's not insured, leave him there." Really?

Though I am conservative, a registered Republican, I must reluctantly affirm that this is just like automobile insurance, which is currently a requirement in nearly every state, and will eventually be a national requirement. If you are alive, you will pay medical insurance premiums. Life is uncertain. You cannot guarantee that you will live fifty years without the need to get medical help. My poor grandmother would be spitting mad at such a requirement. It can't be helped.

I look back at my working career, in which I have had medical insurance since 1967. It has proportionally risen the most in recent years, so I can only give an approximate figure, but in current dollars, the premiums, mostly company paid, total about $400,000. Would I like to have that money in my bank account instead? You bet. But I've had some expensive medical stuff done, so I don't grudge it.

There are bound to be horror stories of all kinds, no matter what kind of medical insurance law we live under in the next fifty years. Our task as a civilized society is to continue to revise laws to minimize the horror stories, and to make right what we can when one occurs. That is what we have done for 234 years so far, with variable success. It beats anarchy.

Monday, January 17, 2011

Had we better eyes

kw: astronomy, photography, atlases

For many years I have dreamed about making a photographic sky atlas. This desire was sparked when I worked at California Institute of Technology (in the machine shop), where one day I was allowed to peruse their copy of the plates from the Palomar Sky Survey. Those plates from the POSS-I Survey, numbered 1,874. Half were "blue" plates and half were "red" of the identical areas. Each plate is roughly six degrees square on the sky.

Not wishing to expose (and pay for) more than 25 rolls of color film, I had the idea of making exposures that would approximate naked-eye views of the sky, but exposed so as to "see" with ten and 100 times the sensitivity of an ordinary eye. Using ISO 1600 film, that would have been 12 seconds and two minutes, ignoring reciprocity failure, or about twice that long to account for it. My scheme would have resulted in a set of about seventy exposures (less than three film rolls) to cover the northern sky and that portion of the southern sky visible from North America.

Time has always been the most deciding factor with me. I would need three or four observing sessions of several nights each, spaced around the year, from a dark location such as the top of a mountain in Colorado. In more recent years, now that digital photography is the norm, I realized that processing costs were now nearly zero, though printing was much the same if I wanted a "book" format. But I couldn't free up the time to go shoot the exposures.

Even more recently, the project has become moot. The successors to POSS-I, completed in the 1980s and 1990s, have been digitized into the Digital Sky Survey and incorporated into the "Sky" section of Google Earth. When you are looking at Google Sky, a notice at the bottom of the screen shows a credit line. Most of the sky is credited "© 2007 DSS Consortium". Some areas of the sky are instead credited to SDSS, the Sloan survey, and a few small bits to STSCI, which holds the images from the Hubble Space Telescope.

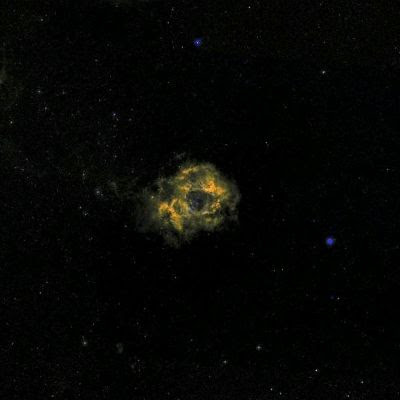

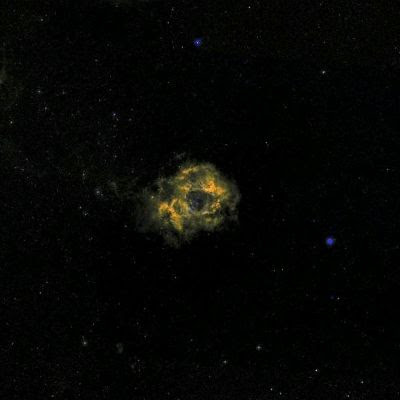

To see how closely I can realize my dream without shooting any film at all, I took a look at a portion of the sky near Orion, centered on the Rosette Nebula:

This image approximates a POSS-I plate pair, combined and colorized. It is about six degrees across. The nebula, which contains the open cluster NGC 2244, is one degree across, or twice as wide as the full moon. It would be a stupendous sight were it bright enough to see without the amplification provided by photography, film or digital. A six degree field of vision is about what you see with 7x to 10x binoculars. However, the next image is more representative of what such binoculars would show you from a really dark location:

This image approximates a POSS-I plate pair, combined and colorized. It is about six degrees across. The nebula, which contains the open cluster NGC 2244, is one degree across, or twice as wide as the full moon. It would be a stupendous sight were it bright enough to see without the amplification provided by photography, film or digital. A six degree field of vision is about what you see with 7x to 10x binoculars. However, the next image is more representative of what such binoculars would show you from a really dark location:

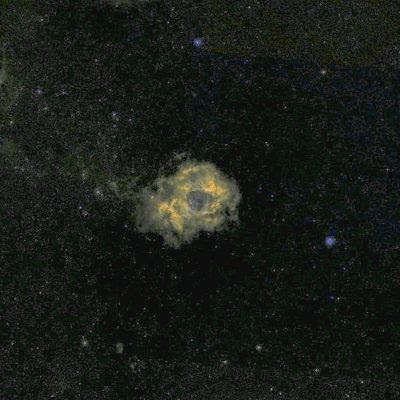

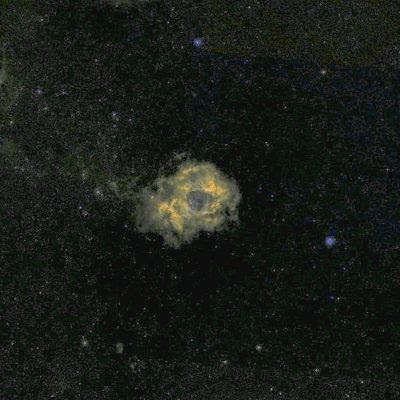

The eye just doesn't have the sensitivity to see more than the brightest bits of such a nebula, though a number of stars would be more visible than what is seen here. I reckon this image is probably a bit optimistic. The Rosette Nebula, as large as it is, wasn't named until it had been found photographically. It is dimmer than the great Orion nebula, the central portion of which is quite distinct when seen with binoculars.

The eye just doesn't have the sensitivity to see more than the brightest bits of such a nebula, though a number of stars would be more visible than what is seen here. I reckon this image is probably a bit optimistic. The Rosette Nebula, as large as it is, wasn't named until it had been found photographically. It is dimmer than the great Orion nebula, the central portion of which is quite distinct when seen with binoculars.

On the other hand, adjusting the brightness of the image upward, we see what would show if the DSS had used a deeper baseline and higher gamma. With just a doubling of effective exposure, a myriad of faint background stars can be seen, and the nebula's details are even more distinct. If we could see this well, though, the sky would be rather confusing. Too much to see!

On the other hand, adjusting the brightness of the image upward, we see what would show if the DSS had used a deeper baseline and higher gamma. With just a doubling of effective exposure, a myriad of faint background stars can be seen, and the nebula's details are even more distinct. If we could see this well, though, the sky would be rather confusing. Too much to see!

For many years I have dreamed about making a photographic sky atlas. This desire was sparked when I worked at California Institute of Technology (in the machine shop), where one day I was allowed to peruse their copy of the plates from the Palomar Sky Survey. Those plates from the POSS-I Survey, numbered 1,874. Half were "blue" plates and half were "red" of the identical areas. Each plate is roughly six degrees square on the sky.

Not wishing to expose (and pay for) more than 25 rolls of color film, I had the idea of making exposures that would approximate naked-eye views of the sky, but exposed so as to "see" with ten and 100 times the sensitivity of an ordinary eye. Using ISO 1600 film, that would have been 12 seconds and two minutes, ignoring reciprocity failure, or about twice that long to account for it. My scheme would have resulted in a set of about seventy exposures (less than three film rolls) to cover the northern sky and that portion of the southern sky visible from North America.

Time has always been the most deciding factor with me. I would need three or four observing sessions of several nights each, spaced around the year, from a dark location such as the top of a mountain in Colorado. In more recent years, now that digital photography is the norm, I realized that processing costs were now nearly zero, though printing was much the same if I wanted a "book" format. But I couldn't free up the time to go shoot the exposures.

Even more recently, the project has become moot. The successors to POSS-I, completed in the 1980s and 1990s, have been digitized into the Digital Sky Survey and incorporated into the "Sky" section of Google Earth. When you are looking at Google Sky, a notice at the bottom of the screen shows a credit line. Most of the sky is credited "© 2007 DSS Consortium". Some areas of the sky are instead credited to SDSS, the Sloan survey, and a few small bits to STSCI, which holds the images from the Hubble Space Telescope.

To see how closely I can realize my dream without shooting any film at all, I took a look at a portion of the sky near Orion, centered on the Rosette Nebula:

This image approximates a POSS-I plate pair, combined and colorized. It is about six degrees across. The nebula, which contains the open cluster NGC 2244, is one degree across, or twice as wide as the full moon. It would be a stupendous sight were it bright enough to see without the amplification provided by photography, film or digital. A six degree field of vision is about what you see with 7x to 10x binoculars. However, the next image is more representative of what such binoculars would show you from a really dark location: