Thursday, June 30, 2005

History of the Imagined Universe

Subject of the times: The history of everything. Now, a history of what people think about the universe: David Park's The Grand Contraption: The World as Myth, Number, and Chance., published by Princeton University Press. The author is Emeritus Professor of Physics at Williams College. I guess it takes a scientist to cover the subject. Stephen Hawking gave us A Short History of Time. This is a short history of cosmology—or at least cosmological speculation for the most part.

Dr. Park has a lot of ground to cover, 4,000 years of speculative and scientific literature, in 300 pages. He has to do a lot of "we need not follow this further"-ing, to avoid producing a 3,000 or 30,000 page tome.

The historical threads begin with the origin of writing, including an illustration of the world according to ancient Babylon, about the time that Gilgamesh was written down.

The greatest impression I received was of the scale of the universe. When Park writes "world," at least in the latter half of the book "universe" is really what is meant...or perhaps "observable universe."

Observable is the key here. Parallax was discovered very early, but the eye is too crude to measure even the Moon's distance with any accuracy. The earliest attempts placed both Moon and Sun within a few times the earth's size, and the "fixed" stars not much farther away. The spherical earth was known to at least some as early as 500 BC, but the initial estimate of its size was quite large: 40,000 miles in circumference. Eratosthenes, a couple centuries later, came as close as anyone prior to the 1800s, with about 23,000 (may be more; we aren't sure how long his stade was) miles.

It took the Copernican Revolution to push the planets farther away than a few tens of thousands of miles. Kepler, using Brahe's data, used oppositions and quadratures of Earth with Mars to determine its distance to be some tens of millions of miles. The invention of the telescope gave observers at least the uneasy feeling that there were distant stars many times farther yet.

Human understanding of the scale of the universe has steadily increased. The "observable universe" is currently thought to have a radius of about 13 billion light-years. However, if you work the math backwards, using current assumptions about the Big Bang and cosmic expansion since, quasars near "the edge", whose 13-billion-year-old light is just reaching us, would today be more like 75 billion light-years away. Park doesn't mention that. He doesn't need to. A discussion of the implications of Alan Guth's "inflation" hypothesis indicate that the size of the inflated bubble was perhaps a billion light-years, at a time when light had only traveled a trillionth of a trillionth of a meter. So we're not seeing much of what's really out there!

In the early part of the book, he necessarily focuses on religious texts. Only they had origin stories. I found it interesting that all of them, with one exception, imagined the world's creation as an act of sexual procreation, usually an act of incest. The exception? The book of Genesis. (someone is asking, "Does that mean you think Genesis is scientifically accurate?" I means that Genesis does not record ridiculous fantasies. As to science, while that isn't the intent of the Hebrew scriptures, another biblical book contains the earliest description of a spherical Earth, with the division between day and night traveling around it as a rotating circle. The terminator, as seen from elsewhere, perhaps... Hang in there, I may get into Bible stuff someday, though that's not the intent of THIS blog).

Resurfacing: the author emphasizes the continuing sense of wonder on the part of discoverer after discoverer. We also see the continuing, negative reaction by insecure traditionalists. Discoveries remain. Tradition loses its power and becomes irrelevant. Real faith needs no tradition. Real science is delighted at each new unveiling of reality.

No matter how big our universe—and remember, for most people, it is no bigger than that of the Babylonians—we all benefit from the chance to look farther, to see more, and to imagine.

Dress Size Deflation

I recently went clothes shopping with my wife. She's petite, a size 8...or that used to be petite. Now it is a "women's size." So is 7. Guess I haven't been to the women's department in a while (a few years? decades??). I sidled over to the other end of the rack. It topped out at 12, and there were few items larger than a size 10.

I remember that "women's" sizes were 12-16. I remember 5-7-9 shops, for the skinniest of girls. Now I've been told, by a high school girl we know, that many, many teenage girls (later teens: 15-19) are sizes 2, 1, and Zero! What's going on?

Two things are going on. One is, today's 8 is 1980's size 9 or 10 (or even 12, depending on manufacturer). That size Zero is really about a 3, in 1980 terms. A "real" Zero would have a 15-inch waist. Dressmakers label their stuff to sell, not to satisfy a mathematician. Little sizes sell.

But the other thing: Many, many young women really are starving themselves down to sticklike, scrawny caricatures. They all want to have a waist under 20 inches. Whatever happened to 36-24-36 as an ideal?

My size 8 wife is about the smallest woman of normal height (she's 5'-3") I can hold, and not feel I'm grasping a 4x4. I prefer seeing women who resemble the beauties in paintings by Rubens or Titian.

A bit of upholstery indicates good health and a good appetite. In 1865, Manet first showed Olympia. It was greeted with disdain. She was a real woman, not some idealized historical figure. And besides, she was too skinny. Folks today think she's a bit chubby, albeit a very pretty chubby.

Girls of all ages, I have a bit of advice. Do you know what's really attractive? Good health. A strong constitution. A cheerful, happy disposition. Cleanliness and neatness. Get out and walk more...and not just in the mall! Spend more time walking than you do watching TV. Wash off the cosmetics so your skin will be healthy. Eat healthy, enjoyable food, but stay away from fast foods. Don't get on a scale more than once a week—monthly or less is even better. Seek out friends who don't betray you, friends who are smart, curious, and upbeat. Drop anybody who gossips too much. Gossip reshapes your face, and not in a good way. Wear clothes that feel good, and you'll look good.

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

Tornadoes and Their Groupies

Mark Svenvold, Fordham University's Poet-in-Residence, spent a summer traveling with veteran storm chaser Matt Biddle, logging 6,000 miles in May, 2004. His book Big Weather: Chasing Tornadoes in the Heart of America (Henry Holt, publisher)s not so much a chronicle as a memoir and meditation. The book has copious endnotes and a good index, but no bibliography.

The first half of May that year was quiet, quiet enough to drive hundreds of storm-chasers half crazy. The second half was anything but. May 22 produced the Hallam, NE tornado, which basically plowed a furrow some sixty miles wide, and as wide as 2.5 miles, the widest on record.

Mark and Matt didn't see that one. The account in the book is from several eyewitnesses (and some scar-witnesses). But they saw plenty of others.

With the phenomenon of storm-chasing, quite a number of allied subjects fall under scrutiny: the classes of chasers (from yahoos to scientists), the advent and rise of the Weather Channel, and possible influences of global warming among them. Actually, it seems in retrospect that a third of the writing is polemical, intended to convince the reader of the reality, not just of global warming, but of human causes thereof.

Plenty of ink, and several photos, goes to Sean Casey and his "Tornado Intercept Vehicle" (TIV), a homemade tank weighing over six tons. Mr. Casey doesn't fit any other category, but is serious enough, and has learned enough, to earn the respect of the operators of the Doppler-on-Wheels (DOW) trucks from the Center for Severe Weather Research.

He was preaching to choir in my case. But I'm one who sees more benefit than loss in that equation. I know the math better than most. We know CO2 has about doubled since 1850. We can figure it has resulted in about a degree or two (F; or half to 1 deg C) of warming. Most of this has been polar. In temperate latitudes, the main effect has been greater variability: longer, warmer spring and summer, colder but shorter winter, with more violent storms more common than before. If the amount of CO2 were increased ten times, the maximum warming would be 4-6 deg F (2-3 C), so there's a limit to what will result just by our burning stuff.

There's just enough photography to whet the appetite. To see more, there are plenty of web sites with thousands of pictures. The cultish reaction many chasers have to images and video of tornadoes prompts the author to call it "torn porn." Probably apt. We tend to be drawn to destruction, and nothing causes greater levels of localized destruction than a tornado. A really big one, an F5, leaves only plowed ground. There's plenty to like about Big Weather.

Friday, June 24, 2005

Tornado Stories

I've been reading a book about tornadoes and tornado chasing. I'll review it soon. It reminded me of experiences going way, way back.

I first heard a tornado story from my grandmother. Her family lived in Wichita, Kansas when she was young. One sunny day, a storm blew up rather suddenly. The young girl, exploring in a hidden corner of the yard, didn't respond to being called right away. A hard wind prompted her to go around to the front of the house, trying to find people—everyone had vanished. She sat on the porch, looked across the street, and saw a neighbor's house shatter apart. The tornado lifted at that moment, and roared right above her. She looked up inside the funnel. She told me it was blue inside, rather bright against the dark sky.

I've heard from others that tornadoes that arrive in dry weather have a lot of lightning with them, including inside the funnel. Some tornadoes are visible after dark for that reason. I have only seen tornadoes in moist or rainy conditions.

As a child, growing up in the arid Southwest, I often saw dust devils. We kids would pretend they were mighty funnel clouds, and imagine being carried away like Dorothy, to Oz. On a few occasions I ran right into one of them. Once it was strong enough to give me a spin and sit me down. I never tried running into one that was carrying a few tumbleweeds, though!

I first saw (nearly) the real thing when I was in High School. I was working at a resort on Lake Erie. One afternoon a big storm protruded a wall cloud, then, one after another, seven waterspouts formed over the lake, spun ashore, and broke up. They were about half a mile away, no more than fifty feet across just above the water line.

I went to graduate school in Rapid City, South Dakota. We lived East of town. People boasted that the city had never had a tornado within city limits. You could see, though, on aerial photos (I was a Geology student) several scars of tornadoes that had knocked over swathes of trees in the Black Hills. One day, the boast became outdated. A huge storm system blew up, with wind of all kinds, but little rain. I looked out my back door and saw a funnel cloud forming, several miles away. I ran outside to photograph it. About then, a blast of wind blew me right back through the open door, into the house. It was the inflow from a nearby tornado. From the front door, we watched a tornado tear its way across a sorghum field, hoovering up about a third of my neighbor's crop. It was later determined that four tornadoes passed through the city that day.

Many years later, living in Oklahoma, I nearly drove into one. Oklahoma twisters tend to be rain-wrapped. Anywhere within a half mile of them, you can't see them. I was at a friend's house, about 5 pm. My wife called to say the tornado siren had gone off (I could hear it over the phone), and would I come home Right Now! Foolishly, I agreed...there was no siren howling near where I was. The traffic lights were all out, so I figured it had already passed on. I found out later, the town power came from the West, and the wires went down ten minutes before the storm arrived. I remember turning North onto Perkins, the main street toward home. It began raining buckets, and blowing hard. Within seconds there was surf in the middle of the street. When it began to hail, I whipped into a parking lot and drove to the lee side of a warehouse market. I'd been trying to find a radio station that was working. Just as gravel from the building's roof began falling on my car, I got a Tulsa station. I heard, "...we have it on radar. It is at the intersection of Perkins and McElroy." I though, "That's where I am!" A minute or two later, the wind began to drop. Within ten minutes the sky was blue, except in the East, where the storm was receding. I had to go around the rest of Perkins Avenue, because there were wires lying in the street. The power poles had all been broken off about 15 feet above the ground, and the upper floor of a 2-storey apartment building, right across the street from my shelter, had been removed. It seems the tornado wasn't quite on the ground when it went by me, about 100 yards away.

Five years later, we took a driving vacation through Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. On the road going West toward Goodland, Kansas, we saw an isolated storm get organized about twenty miles further on. Goodland was another twenty miles beyond that. It was similar to the Ohio experience, but not waterspouts. There were five tornadoes in all, and for several minutes at a time there would be three on the ground, apparently following the same track. About the time the one in front broke up, another would form at the rear. They looked like small tornadoes, perhaps F0; I don't think they were as big as F1. See The Fujita Scale of Tornado Intensity. Regardless, I slowed down, not wanting to get there too soon! After about fifteen minutes, the show was over and the storm broke up. Another fifteen minutes, and we drove by, seeing only a few "drag marks" on the ground showing where the funnels had crossed the highway.

The following year, we moved to the East Coast, where tornadoes are not impossible, but very scarce. Funny, though, we liked Oklahoma a lot, and talk about returning when I retire.

Wednesday, June 22, 2005

And You Thought Prime Numbers Were Dull

Am I a glutton for punishment, or what? My career is on the fringes of mathematics, mainly algorithmics. I have a dilettante's interest in quite a variety of mathematical disciplines. But those weird critters called "higher mathematics" are so far beyond my ken...

Well, I found myself reading almost compulsively, as I made my way through Stalking the Riemann Hypothesis by Dan Rockmore, published by Pantheon Books. I didn't count them up, but I think Dr. Rockmore touches at least fifty realms of mathematics with which I have little or no experience. He shows how all of them build on one another, how all are linked in various (and to me, abstruse) ways, and how all—and others—will be needed to prove the Riemann Hypothesis.

Rockmore explains just enough of number theory, the hierarchy of numbers, logarithms, calculus, topology, and a host—a big host—of other aspects of math so a moderately educated reader can at least follow where he is going. Not many will really understand, but it is like following a guide who can tell you more detail about every flower, bug, waterfall, and rock than you'd ever absorb. You pick up enough to enjoy the landscape a bit better than before.

He also presents capsule biographies of a few dozen people who have contributed to the understanding of the Riemann hypothesis, the connection between his "zeta zeroes" and the "zeta zeroes" of many, many other mathematical systems. He is a great example of a scientist who not only writes well, but can tell a good story.

One might say this book is premature. The hypothesis hasn't been proved, so...what's the big deal? For one thing, I realized that, if the hypothesis is ever proved, at least a (very) few people will have a deep and clear understanding of the deep structure hidden in the endless parade of prime numbers.

It all centers on efforts through several centuries to improve, and prove, the Prime Number Theorem (Here is the Wikipedia discussion). Very basically, the number of primes less than n is estimated asymptotically to be n/ln(n). For n = 100, this gives 21.7 → 22. There are actually 25 primes smaller than 100. For n = 1016, n/ln(n) yields 271,434,051,189,532 and change; the actual number is 279,238,341,033,925. The discrepancy is 3%.

Gauss took the approach of integrating this function, which produces much greater accuracy, in the range of 0.01% or less. Riemann used complex analysis to produce a function with an infinite number of zeroes, or roots: values for which the function produces zero. A major, infinite, family of these zeroes lie on a vertical line in the complex plane, with a real component of 0.5; to prove the Riemann Hypothesis amounts to proving that all of the zeroes of interest fall on this line.

Appropriate computations with this function reproduce the prime accumulation curve very exactly. An example in the book shows how well it works for primes less than 230. The kicker, IMHO, is that the close correspondence shown required doing computations using the first 500 of Riemann's zeta zeroes. If this trend holds, it seems to me that actually finding primes by using Riemann's function requires much more computation than any way in which we do it now

However, the value in finding a proof is that the existence of the proof would show that there is an underlying order in the sequence of prime numbers, beyond the obvious one embodied in the sieve of Eratosthenes: this explanation at The Prime Glossary is better than I can devise. Basic take-away message: the farther you take "the sieve", the more prime divisors are needed, so the ranks of primes get thinner and thinner as more groups of multiples are removed.

I give Dr. Rockmore great credit for understanding the many corners of the math landscape well enough to make them, if not fully understood, certainly quite satisfying conceptually and enjoyable to contemplate.

Tuesday, June 21, 2005

Andre Norton (1912-2005)

Last week I read Echoes in Time, the sixth of seven "Time Traders" novels by Andre Norton—this one co-written with Sherwood Smith. Then today, while looking up the Andre Norton Bibliography website, I found this notice of her recent passing: Andre Norton (1912-2005) - SFWA News. She passed away May 17, 2005, age 93.

The seven Time Traders titles were written from 1950 to 2002. She knew how to return freshness to earlier ideas. Echoes in Time was released in 1999. I like Norton's handling of time travel, that one cannot self-loop. Rather, after spending a week in the past, one must return a week later than one's departure. This, and confining the story line to time trips over centuries rather than shorter intervals, avoids the paradoxes that many authors either fall afoul of, or must resort to a lot of "I had to do that, because it was already done in the future" to gloss over (Harry Potter's saving himself from Dementors via a time loop is a case in point).

The machinery that accomplishes time travel, and the spaceships, are products of alien technology, ultimately stolen from them. The notion that these "aliens" may be human descendants is brought up, and not quite solved in the novel. The short war between these (possible) aliens and others, including humans, is also shown to be a perfectly understandable response on the part of the owners of the technology to their theft.

Other ramifications, including the gene-twisting entity that makes other questions moot, I'll leave you to read for yourself.

Friday, June 17, 2005

Differential Calculus 001-A1: The Differential Formula

To my summer math students

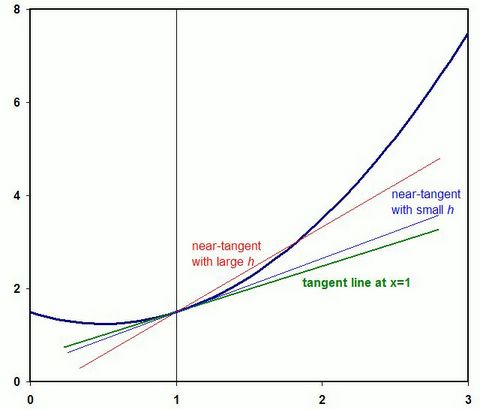

We use Differential Calculus to produce the D operator. The D operator acts on a function to produce another function that expresses the slope of the first function. We'll sneak up on it by way of example, using this graph.

Approaching the Tangent

We want to find the slope of the black curve where the x coordinate is 1.0; a line having this slope is tangent to the curve as shown by the green line. If we know the function y=f(x) that produced the curve, we can estimate the slope by figuring y at x=1, then choosing a nearby point x+h, or 1+h in this case, and figuring a new y=f(x+h). Then we can take the difference in y and divide by the difference in x (which is h) to get an approximate value for the slope. The formula is thus:

slope ≈ [f(x+h) - f(x)] / h

If h is relatively large, the estimate will be less accurate than when h is small. The red and blue lines on the graph illustrate this. However, if h is very small, we will find that rounding error causes some loss of precision also.

For the curve above, here are estimates of the slope calculated for different values of h:

h = 0.500, slope = 1.500

h = 0.250, slope = 1.250

h = 0.125, slope = 1.125

This curve was chosen to make it easy to show that the slope approaches 1 when x=1 and h approaches zero. We express this situation with a limit statement:

slope = lim{h→0} [f(x+h) - f(x)] / h

The beauty of this expression is that for many functions, the algebra works out so that an h in the numerator cancels out the h in the denominator, so you can then set h to zero to get a new function that expresses the slope you want, for any value of x. Here is how it works for a simple monomial. We'll use y', or "y-prime", to refer to the new function that was derived from the original function.

y = x3

y' = lim{h→0} [(x+h)3 - x3] / h

Now, (x+h)3 = x3 + 3x2h + 3xh2 + h3

Thus [(x+h)3 - x3] / h = [3x2h + 3xh2 + h3] / h

Note that every term in the numerator now contains h, so we can cancel to get

y' = lim{h→0}[3x2 + 3xh + h2] = 3x2

So we assert that the slope of the function y = x3 is y' = 3x2 at every point. We'll explore more polynomials and their derivatives, or slope functions, in a later post.

Now, a word on nomenclature.

The differential formula is so called because it calculates a difference, though it reduces the range of that difference to zero. It can operate on a point to produce a slope at that point. But mainly, it operates on a function to produce another function. The second function is derived from the first, so it is called its derivative. For many functions, the derivative also has a derivative, called the second derivative of the first function.

There are three common ways to express the operation and to label the derivative. These arose because several different people developed the method, and each invented his own symbolism. They are retained because they are each useful in various situations.

Prime notation: the derivative of function y is y', or the derivative of f(x) is f'(x). These are pronounced "y prime" and "f prime of x". The second derivative is shown with a double prime: y" or f"(x), pronounced "y double prime" and "f double prime of x".

d/dx notation: the derivative of function y is dy/dx, or that of f(x) is df(x)/dx . These are pronounced "d y d x" and "d f of x d x". The second derivative is shown by an exponent; this makes this notation more useful for third and higher derivatives. d2y/dx2 and d2f(x)/dx2 are pronounced "d squared y d x squared" and "d squared f of x d x squared."

D notation: the derivative of function y is shown as either D(y) or Dx(y), depending on whether one needs to explicitly show that the derivation is with respect to x (it could be with respect to t, for example, instead). Higher derivatives are shown as an exponent on the D only. This notation is seldom used with a function shown as f(x), because of multiple parentheses.

For each notation, the formal operator is the prime, the d/dx, or the D, respectively.

Thursday, June 16, 2005

We are all made of the same stuff (even doctors)

Beacon Press has published a delightful account of a Doctor's real education at the hands of her "patients." The title of this post is from the last phrase of the second chapter/essay/story (it is a wonderful sign when you can't quite classify a document, yet find it compelling reading).

Dr. Danielle Ofri, in Incidental Findings: Lessons from My Patients in the Art of Medicine gathers story/essays she's published over a decade or so, and a few current stories written "in real time." She didn't become an Attending Physician at New York's Bellevue Hospital by following any beaten path. She made her own path. After earning MD and PhD, and completing a residency at Bellevue, she alternated travel—mainly in Latin America, turning schooldays Spanish into a real second language—with temporary assignments at clinics in several small towns, whose locations fairly bracket the US.

Despite the overwhelming pressures on this generation of physicians, to run patients through in as assembly-line fashion as possible, to distance oneself from immense suffering, she has frequently made human connection with one person after another, going beyond "learning the human body" to learning the human.

From a woman whose terrible acne expresses her crushing poverty and abuse; to a suburban girl struggling with an abortion decision; to a once-prominent man reduced to a frail shell, yet having lost none of the drive—nor intolerance for fools—that made his empire; Dr. Ofri learns from them all, "...to envision patients beyond their role as sick people."

Wednesday, June 15, 2005

Parting Shots by Holmes

I've finished reading The Essential Holmes by R.A. Posner. A few more quotations I found interesting (offered without further comment):

- To Harold Laski, Dec 9, 1921; on beliefs and metaphysics: "The inevitable is not wicked. If you can improve upon it all right, but it is not necessary to damn the stem because you are a flower."

- To Laski again, May 21, 1927; on social trends, arguing contra socialism: "...as I said the other day, the only contribution that any man makes that can't be got more cheaply from the water and the sky is ideas—the immediate or remote direction of energy which man does not produce, whether it comes from his muscles or a machine. Ideas come from the despised bourgeoisie not from labor."

- Speaking to the Harvard Law School Association, Feb 15, 1913: "I should like to see it brought home to the public that the question of fair prices is due to the fact that none of us can have as much as we want of all the things we want; that as less will be produced than the public wants, the question is how much of each product it will have and how much to go without; that thus the final competition is between the objects of desire, and therefore between the producers of those objects; that when we oppose labor and capital, labor means the group that is selling its product and capital [means] all the other groups that are buying it. The hated capitalist is simply the mediator, the prophet, the adjuster according to his divination of the future desire. If you could get that believed, the body of the people would have no doubt as to the worth of law."

- From "Natural Law" in Harvard Law Review (1918), on the limits to argument: "Deep-seated preferences cannot be argued about—you cannot argue a man into liking a glass of beer—and therefore, when differences are sufficiently far reaching, we try to kill the other man rather than let him have his way. But that is perfectly consistent with admitting that, so far as appears, his grounds are just as good as ours."

- And finally, again to Laski, Feb 1, 1919; on common sense and common law: "A man who calls everybody a damn fool is like a man who damns the weather—he only shows that he is not adapted to his environment, not that the environment is wrong."

Monday, June 13, 2005

Schneier on Security: Attack Trends: 2004 and 2005

Have a look at this post by Bruce Schneier:

Schneier on Security: Attack Trends: 2004 and 2005

We have reached a situation in which our machinery is subject to the same threatening environment as any biological species. Both pathogens and immune systems—of the digital persuasion—are in an arms race that will spiral onward, probably without limit.

It may seem that there is a conceptual difference: computer viruses, worms, and spyware (and other varieties even now being ideated) are produced by programmers. To my way of thinking, the worm-writer is a part of the system, and bears the same relationship to the software that an animal body and mind bear to the selfish DNA upon which their existence depends.

Sunday, June 12, 2005

Reparations Nonsense

The news in the Philadelphia area is all about "slavery in the background". It seems some folks I decline to name want businesses to delve into their pasts and reveal anything related to slavery about the way their business was run, I guess prior to 1865. Well, considering that the fraternity of companies aged 140+ numbers about five, this can be seen as rather discriminatory in itself.

Further, the notion of paying reparations to the descendants of slaves is coupled in. I wonder just how many U.S. Citizens aren't descended from slaves, somewhere along the line? I am, though the connection is rather tenuous. It seems someone named Turner was manumitted in the mid-1700s and found his way into my family tree. Of course, when the name Turner was discovered by my very prejudiced great aunt from Missouri, while carrying on her genealogical hobby, she stopped looking along that line.

But there are other places in her records where an ancestral line stops in an odd place. The name Barraclough comes to mind. It arose as a French transliteration of the name Bear Claw. An Iroquois who learned English, then French, liked the sound of Bear Claw better than Griffe-d'Ours. So, though I have significant ancestors who arrived on the Mayflower, I also have one or two who were there to see it arrive.

Yet, I am about as white as one can get with mainly Western European ancestors. About half Scot (both Celt and Anglo-Saxon), perhaps a quarter German, lesser amounts of English (Anglo-Saxon) and Irish (Celt), plus the aforementioned African and Amerind threads.

Let's look at the Germanic peoples here, the Anglo-Saxon and homeland German folks that make up more than half of my family tree. 1200 years ago, they and an amalgam of former Roman peoples were united politically, and spent a few centuries intermarrying. From the First to the Fifth Century, the various Roman subjects had also intermarried pretty freely, including quite a number of Africans, both light (Egyptian) and dark (Ethiopian and Libyan) skinned. As a result of that and the later intermarrying after Charlemagne (also an ancestor of mine), I've been told that the average "European" today is about 1/8 African, somewhat lower in Northern and Eastern Europe, somewhat more to the South and West.

So, based on my known genealogy, I have a small fraction of a percent of African blood of more recent vintage. Based on broader historical indicators, there is probably another 6-8-10% Africa in there, so well mixed in that I "look white."

So, if more reparations get mandated, we'll really have a case of those who don't look that African (though they are, at least a little) making reparations to those who seem to be more so.

Another thread. On my Father's side, my ancestors in the 1700s and later were Methodists (as I was raised). On my Mother's side, from the 1500s to about 1900 they were Quaker, then later Methodist. Members of both sides of my family carried on Underground Railroad activities, mainly from the 1780s onward. Do the offspring of abolitionists need to pay reparations to the offspring of slaves they helped set free?

Plain fact: More Euro-American alive today are descended from anti-slave than pro-slave families. The real thing people want reparations for—this isn't mentioned out loud—is the century of Jim Crow laws. But we know pretty well who carried that on...the parents and grandparents of many of the same folks who are the loudest (white) proponents of reparations today.

Guilty conscience for lunch, anyone?

Just how far will this silliness go?

Friday, June 10, 2005

Holmes on Life and the Past

More from Oliver W. Holmes, Jr.

- To Lewis Einstein, Jul 23, 1906; on life: "...life is painting a picture not doing a sum." I have seen this elsewhere in his writings. It resonates with me, because of my tendency to look at the vicissitudes of life as problems to be solved rather than as part of a picture; if they trouble me, the best I can often do is manage them. They cannot be "solved."

- To Harold Laski, Aug 24, 1924; on judging the past: "If I may quote myself we must correct the judgment of posterity by that of the time."

- Obituary of George Otis Shattuck, 1897; the passage he quotes above: "People often speak of correcting the hudgment of time by that of posterity. I think it is quite true to say that we must correct the judgment of posterity by that of the time." How often we see people condemning past figures for actions and attitudes that seem offensive to some today, but were either perfectly reasonable in the context of their own times, or were indeed noble compared to the times.

I can think of no better example of the latter than the way certain folks condemn Jesus or one of his apostles for a saying about women or slaves. Such folks do not realize that Jesus did more in his time to elevate women above their chattel status. Nor that Paul, in particular, while exhorting slaves among the believers to refrain from struggling against their condition (for the alternative was imminent death), yet wrote a very touching letter to Philemon, whose runaway slave Onesimus had become a believer, in which he tugs every lever he can reach to persuade Philemon to release the slave. I am sure Onesimus was very wary of carrying this letter back to his master, but history attests that he was freed as a result. Paul was a practical abolitionist.

Thursday, June 09, 2005

Fantastic Voyage redux

I checked out Fantastic Voyage: Live long enough to live forever by Ray Kurzweil and Terry Grossman. I perused the table of contents, read scattered items here and there, but didn't go further. The writing is done well enough, but most of the info is old hat. So is the notion that unlimited lifespan is just around the corner. Somebody-or-other makes such promises—and gains enough publicity to make a bit of a splash—about once a generation.

As has been said before, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Of the latter, sadly, there is next to none. Again, I haven't looked at a great deal of the book. But I have perused enough to get this impression: The main claim is based on extrapolating the trend of average life expectancy since the 1880s or so.

I am sure we've all heard, "In 1900 people lived less than forty years; now they live to about eighty." There are so many fallacies in these fourteen words I can only touch the most egregious. The average life expectancy at birth in 1900 was (depending on your source) somewhere between 35 and 40 years. However, infant mortality was so high, that if you dig, you can find out the following, all for 1900:

- Average life expectancy for five-year-olds was about sixty.

- Average life expectancy for twenty-year-olds was above seventy.

- There were a few hundred-year-olds around, but nobody known was older than 115.

I'll just mention that one of my ancestors, Peregrine White, born aboard the Mayflower in 1621, lived to be 99. But only 1/3 of white children born in the Plymouth colony in the 1620s lived to adulthood.

The situation is this: advances in public health since the American Civil War have greatly reduced "early death", but haven't made much of a dent in the outer boundary, the maximum life span. In fact, in the whole Twentieth Century, only two people are known to have lived more than 118 years, and neither was American: a Japanese monk, and a saucy French woman (who claimed she tried to seduce Vincent Van Gogh).

All that said, Kurzweil and Grossman's book has plenty of useful advice about proper diet and exercise. It has a major section on the need for mega-vitamin doses "for most people," claiming nearly all of us have one or more defective digestive enzymes. I dunno. Some vitamins are toxic, especially the B complex, so you have to do a lot of research before you go on a mega-regimen. That's all I'll say on that.

A final note: What does Kurzweil have to do with this anyway? He is one of the great inventors of our time. Does that qualify him to have medical authority? Not at all. I think he's a name that can get the book past the editors at Rodale. Dr. Grossman has been working longevity research a long time. But the results he reports simply don't support the claims the book makes. I sure wish they did!

Wednesday, June 08, 2005

Vertical Titling

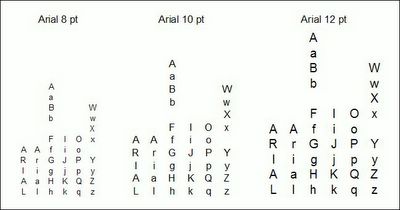

I often use vertical titles on narrow columns. The image below shows how Arial looks when arranged vertically. The image in the following post shows a new font I produced to make vertical titles that look better (to me at least) and takes less space. I began with an existing Sans Serif font that has a large "x" size, then removed nearly all the ledding and centered the lower case. The only letter I had to adjust was the "j".

Vertical Text in Excel using Arial Font

Vertical text example

Holmes Quotes

A few lovely quotes encountered while reading Richard A. Posner's The Essential Holmes, a collection of writing by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. I'm in a section of letters just now. Keep in mind that Holmes was born in 1841, so was 70 in 1911.

- To Frederick Pollock, Dec. 1, 1925; of a legal opinion he was writing: "I am...preparing small diamonds for people of limited intellectual means."

- To Patrick Sheehan, Nov. 23, 1912; of those over-concerned with social consciousness: "To prick the sensitive points of the social consciousness when one ought to know that the suggestion of cures is humbug, I think wicked." (It reminds me that Jesus said, "The poor you will have with you always." Jesus didn't advocate "programs" to relieve the poor, but expected each person acting in wisdom and good conscience to relieve any poverty he could.)

- To Harold Laski, Dec. 31, 1916; of Cicero and his confrères: "It did those chaps a lot of good to live expecting some day to die by the sword."

- Later in the same letter; of those who believe we need to be regulated in everything: "...I don't have sufficient respect for the ability and honesty of my neighbors to desire to be regulated by them...I do believe in The fable of the Bees." (See Mandeville's Fable of the Bees at a site maintained by Maarten Maartensz).

Tuesday, June 07, 2005

NEBULA 2005: More Stories

This continues a post on June 6, 2005.

- "What I Didn't See" by Kary Joy Fowler. On the surface, Alternative History; underneath, "what do we really percieve." A "gorillas in the mist" setting. Much is implied, so reading this takes plenty of thought.

- "Quarks at Appomatox" by Charles L. Harness. Alternative History, or perhaps a decision point that could have led to one. I can't put anything here without giving too much away...

- "Of a Sweet Slow Dance in the Wake of Temporary Dogs" by Adam-Troy Castro. Outer-edge stuff, on the SF-F boundary, where the "S" clearly means "Speculative". The "dogs" are the "dogs of war." Can chaos be scheduled?

- "Goodbye to All That" by Harlan Ellison. You can't classify Ellison. Neither can you read him unless you are exceptionally alert. Like many by Ellison, going to heaven (or hell) has unexpected side effects.

- "The Speed of Dark (Excerpt)" by Elizabeth Moon. A very synoptical chapter of the book. This could be considered mainline fiction, based on this chapter alone. I don't know where the rest of the book goes. It treats autism very sensitively, from the inside.

- "The Empire of Ice Cream" by Jeffrey Ford. Solipsistic fantasy, at one level; dream sequence at another. Synesthesia is the atmosphere, and an extension thereof the theme.

I seldom read the essays or poems in a NEBULA collection. I did read Barry Malzberg's essay "Tripping with the Alchemist," about the Scott Meredith agency and his multilayered association with it. Malzberg's stories are easier reading than this essay.

I like poetry, and I write poetry. Why don't I read the Rhysling Award winners? Because I don't like all poetry. I prefer a poetic work to have both rhyme and rhythm. It's been years since a Rhysling Award went to a poem that you could put to music.

I understand blank verse, and can read Shakespeare, but I don't care at all for free verse, which to me isn't verse at all. Being ultraconservative to the point of autism myself, I prefer structure, rather than prose with poetic figures, broken into lines at odd places. I takes a really superb example of free verse to gain my grudging admiration.

Monday, June 06, 2005

Can "Honorable Computing" work?

In the story "0wnz0red" by Cory Doctorow, the concept of "Honorable Computing" is introduced. A part of the system is a crypto chip in, literally, everything that can compute. Anything you want to download goes through a cryptographic handshaking, so the source knows the identity of the downloader. Once downloaded, and licensed for, say, a certain number of uses (and appropriately paid for), that file works that exact number of times. Suppose it is a music or movie file. It will only "play" on an HC-enabled video or audio system. Not only that, all the crypto attestation that goes on ensures that the computer that is straming the file is not actually an emulator of a computer system that is running on a big UNIX server, which is set up to intercept the bits and retrieve the "clear message" of the licensed product.

All this is supposed to prevent implosion of the $50 Billion entertainment system. Now, that is chump change to the Pentagon, but it is a big deal to the media moguls. Anyway, such a setup would supposedly dry up the supply of pirated material, making peer-to-peer file sharing infeasible. Well, the story is about something else, so this is cool backdrop. But it does bring up the point: how can intellectual property be protected?

To quote Doc Smith of the "Lensman" series: "Whatever technology can create, technology can duplicate." That whole series was based on the "Lens," which was created by Arisians—benevolent, godlike creature—using mind power alone. A Lens attested to the identity of the bearer, so that the galactic police could authenticate one another with 100% reliability. That done, the human-Arisian alliance set about to destroy all the evil races in the galaxy, which lived in Jupiter-like planets. Drat those "poison breathers" anyway!

Just for fun, suppose HC were produced. There is still a bit of wire somewhere, between the last chip and the speaker. A "squid" device can grab the signal via magnetic induction. Appropriately sensitive electronics could even detect the step-levels in the analog reconstruction of the digital signal, and so re-create the digital source with near-perfect reliability. Or, if you are like me, and don't mind speaker-to-air-to-microphone-to-DAT recorder quality, you have a simpler, cheaper solution.

Whether music and video piracy is moral or not, isn't the point. The fact is, there is no way to dry up the source.

NEBULA 2005: Stories

Just to get on the NEBULA ballot, a story's writing must be superb. Very high quality and novelty of the ideas, or at least novelty of treatment or setting, is also assumed.

- "The Mask of the Rex" by Richard Bowes: Fantasy, as pure as it gets. A family's generations of interaction with the gods of mythology, via a mysterious series of priests.

- "The Last of the O-forms" by James Van Pelt: SF, future dystopia. Mammals have begun to mutate and hybridize at incredible rates. What's a traveling zoo to do when its weirdest creatures aren't weird enough any more?

- "Grandma" by Carol Emshwiller: Borderline. Do superheroes have offspring...do they get old...do they die?

- "Sundance" by Robert Silverberg: SF, with a psychological twist. Aliens so mysterious, is making way for human colonists extermination or genocide...and how can the humans know they are still human?

- "Lambing Season" by Molly Gloss: SF, of a very old species. An alien contact story that makes a difference to one person (and to one alien), no others.

- "0wnz0red" by Cory Doctorow. SF, on the borderline of the maybe possible. Those are zeroes in the title. I guess I don't know postmodern cyberpunk hacker slang as well as I thought...unless the author made some of it up on the fly. The implications of cracking the "compiler" for one's own DNA, or something like that. Also introduces a smash hit of an idea: "Honorable Computing." Supposedly the ultimate solution to piracy of entertainment media. I'll rant on this later.

- "Knapsack Poems" by Eleanor Arnason. SF, of a favorite sort--to me. No humans appear. The protagonist and all players are of a species in which all the "singular" pronouns refer to a collective entity with a few to a dozen or so bodies.

- "Coraline (Excerpt)" by Neil Galman. "Hidden Doorway" fantasy. The first three chapters of a novella published as a novel elsewhere.

Saturday, June 04, 2005

Agatha Raisin: Not my Favorite Sleuth

Just prior to beginning the NEBULA awards book I'm reviewing (piecemeal), I read an "Agatha Raisin" mystery by M. C. Beaton. It reminded me why it's been so long since I read one before (the first time). Beaton is a fine, facile writer, and is well-regarded with good reason. But this protagonist, Ms Raisin is a rather unpleasant person: blunt, rude, and moody. She's all-too-prone to falling in love, with nearly any man she meets. There is more dramatic tension in the books from this tendency, than there is from the detective work. She solves crimes by dint of persistence alone, being quite without talent. Maybe that makes her a sympathetic character to many of us. We can't all be a know-it-all like Holmes, Wolfe, or Poirot.

Hedges

Since moving to the East Coast, for the past ten years we've been the proud owners of a privet hedge-nearly 300 feet thereof! Being do-it-yourself sorts, we bought an electric hedge trimmer and a set of hand hedge shears.

Five months of the year, we need to trim this monster, monthly at the very least, and every three weeks is actually better for the plants. Since we do a section at a time, as we're able, it takes nearly the month to get done, at which time we start over. My wife doesn't like to use the electric, so she actually does quite a lot of work with the shears!

I won't belabor it. Suffice it to say, I'll never buy a house with a hedge again.

NEBULA Awards Showcase 2005

The NEBULA Awards books present the best of the best, as judged by a panel of SF&F writers. Been doing so since 1965. This volume is the 41st. The first I read was the 3d, in 1967.

I've observed vast changes in "science fiction" over forty years. The most significant was the gradual merger of Science Fiction with Fantasy, mostly accomplished during the 1990s. To my observation, it began when SF began calling itself Speculative Fiction, late in the 1970s. Prior to that, SF and F were often at enmity. There is still a valid criterion: the former genre is based on known or reasonably extrapolated science, with one or two "impossibles" thrown in, such as faster-than-light travel or time travel. Once the rules of engagement are agreed on, the story proceeds accordingly. By contrast, fantastic fiction is usually, well, fantastic. Fresh problems that the protagonists face are often solved by something quite out of the blue. One doesn't know the rules of engagement from the beginning. I might here observe that life seems to work this way more often than not...

One thing I really don't like reading is "sword and sorcery". Someone once observed that in S&S, the hero must be "very, very strong; very, very brave; and very, very stupid." As a person who lives in my imagination, who lives by his wits, and who was the classic 4-eyed nerd, I find S&S heroes more akin to playground bullies than to anyone with whom I'd like to share an evening by the fireside. My kind of hero is Dick Feynman or Stephen Jay Gould.

Nor do I like stories that don't resolve to some kind of conclusion. I like stories that go somewhere. In a satisfying story, transformation occurs. I have a proverb: All literature reveals its author; good literature lets us see our world; the best literature helps us know ourselves, and become better.

So, how does the present volume stand up? At the moment I've read 1/3 of it, five stories. I've skipped the essays, but will get back to them. I'm pretty pleased. Of course, the writing is stellar, compelling. One of the five is very close to an ultra-classic theme (I'll come back to that in a later post). I'd say, regardless of one's taste, the power of the story-telling in this volume makes it worth the read.

I'll review individual stories in later posts.

Friday, June 03, 2005

Toastmaster at Lunchtime

Why would a 30-year veteran of public speaking join a Toastmasters club? From time to time, I've been a sought-after speaker. My siblings and I were raised to speak. Seven years ago, I joined up. What has changed? I speak better in these ways: fewer "um" and "ah"; better gesture control (I was too histrionic before); and simpler organization of my speeches.

Now, why didn't I do this decades ago? It took this long (two total career changes and several moves to different states) to find a convenient club that I could "brown bag" at lunchtime. All the TM clubs I found before met in the evening, at a restaurant, where one was expected to buy a meal. I am a wimp when it comes to resisting the guilt trip...